C-119 Crash Outside Huntingdon, Tennessee

February 26, 1954

It

was a warm winter day in West Tennessee, with temperatures in the 50s

and moderate winds of about 8 MPH out of the south at McKellar Field,

an airport some forty miles to the southwest. Some people were working

outside; Mr. Homer Demoss, who lived a few blocks west of the Carroll

County

Courthouse, was working in his garden along with his colored hired

hand. T.W. Woods,

a US Naval Aviation veteran who had served as an aerial engineer on

Navy transports, was

working in a field just west of town about 200 yards to the left

(facing toward town) of the bridge on US 70 over Beaver Creek, a

tributary of West Tennessee's South Fork of the Obion River. Ernest

Smith, an Army Air Forces veteran who had become an aerial gunner on

B-17s and B-24s after washing out of pilot training, was about 1/2

block

from the northwest corner of the courthouse, along with Maurice Bunn,

standing on a ladder in the back of his truck. Royal Crider, a

bombardier in the Air Force Reserve in Memphis who had also washed out

of pilot training, was working in the post office just south of the

courthouse on Court Square. William West, an Air Force Reserve

navigator, was standing back of the funeral home about two blocks east

of the courthouse where Huntingdon Mayor Robert Murray was trying a

case. Huntingdon police chief George Hobbs was west of town on US 70

headed toward town. Other witnesses were at various points around

the vicinity of the courthouse. I myself was about twenty miles away at

Lavinia Elementary School in the southwest corner of the county no

doubt waiting impatiently for the bell to ring. I was a third grade

student and had just turned eight the previous November. As the son of

a World War II bomber crewmember and the nephew of an Air Force pilot,

I had a much stronger interest in aviation and airplanes, which to most

children my age were a curiosity. Other kids all

over the county and in Huntingdon were in their own schools gathering

up their things to

get ready to board the bus when the school bell rang in a few minutes.

It was Friday afternoon and everyone was looking forward to two days of

no school. No one had any inkling of the horrible tragedy that was

about to take

place in the winter skies over Huntingdon.

Earlier

that day US Air Force 1st Lieutenant Jack Jenkins and his crew, all of

whom were relatively new to the Air Force and to flying, took off from

their base at Lawson Air

Force Base adjacent to Ft. Benning, Georgia on what was supposed to be

a local training flight. Lt. Jenkins' orders were to spend an hour

practicing maximum performance landings there at Lawson then to

proceed to Brookley Air Force Base at Montgomery, Alabama to fly ten

practice ground controlled radar approaches (GCA). Upon their

completion he was to proceed to Columbus, Georgia airport and practice

Variable

Omni Range (VOR) approaches to finish up the six-hour training flight.

Lt. Jenkins never accomplished any of the assigned tasks - instead, he

took his crew in their nearly brand new C-119G - the airplane only had

110 hours on it - and proceeded northwest to his hometown of

Huntingdon, Tennessee to buzz the town. It turned out that he had done

the same thing two weeks before, on February 9. Although someone

complained to the Tennessee Highway Patrol, Federal aviation

authorities in Nashville later claimed they were not notified of the incident.

Lt.

Jenkins, who was known to his family and friends as Jackie, had grown

up around Huntingdon and graduated from

Huntingdon High School, probably in 1946 or 47 since he is reported to

have graduated from Bethel College, a Cumberland Presbyterian school in

nearby

McKenzie in 1951. While he was in

college. the Korean War broke out and Jack Jenkins joined the Air

Force immediately upon graduation. He applied for pilot training, which

he completed on June 21,

1952 and was rated as a US Air Force pilot and commissioned as an

officer. He was assigned to the

314th Troop Carrier Group at Ashiya, Japan where he spent the next year

flying as a copilot on C-119 Flying Boxcar transports on missions into

and over Korea. Upon completion of his overseas tour, he returned to

the United States and was assigned to the 777th Troop Carrier Squadron,

one of three squadrons of the 464th Troop Carrier Group at Lawson Field.

The 464th had been a bomber group during World War II flying B-24

Liberators from its base in Italy. The unit deactivated after the war

then reactivated at Lawson Field as a troop carrier wing in February,

1953. Lt. Jenkins joined the 777th in August. Although he was an

experienced pilot, he had less than the locally-required 1,000 hours for

assignment as an aircraft commander. Upon reaching that milestone, he

was upgraded and assigned as a first pilot, or aircraft commander, on

the C-119 in January 1954. However, Air Force records indicate

that he was an extra pilot in the squadron and had yet to be assigned

his own crew due to a shortage of qualified crewmembers.

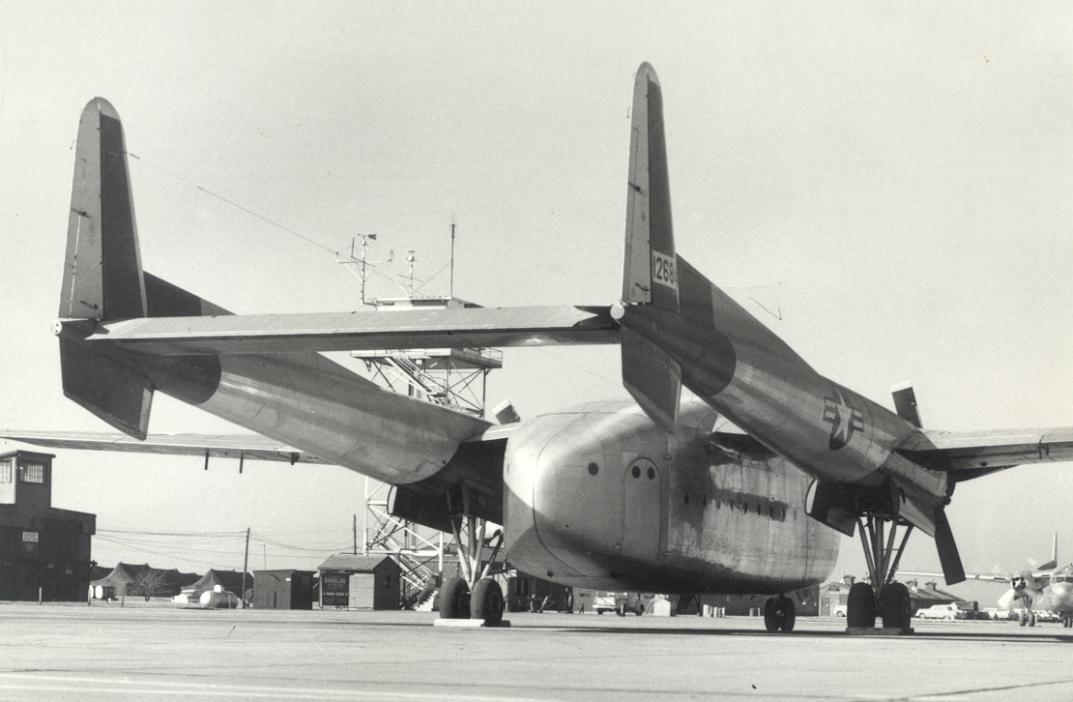

On the day of the crash, Lt. Jenkins was flying with an inexperienced crew. His copilot only had a little over 400 hours, of which only about 50 was in the C-119. The flight engineer was equally inexperienced, with only a little over 50 logged hours. The second engineer was brand new to flying status. Lt. Jenkins himself had logged 1,188 hours, of which some 400 was in pilot training and most of the rest was on combat missions in Korea where the Flying Boxcars, as the C-119s were commonly called, were heavily involved in delivering cargo to remote airfields and dropping by parachute. His flight records show that he had just under 30 hours in B-26 bombers and another 19 or so in C-46 transports. All four of the crewmembers were in their early to mid twenties - Lt. Jenkins was 24. During the subsequent investigation, Lt. Jenkins was identified as an exceptional pilot with sound judgement - and had shown no indications that he would do what he did that tragic day. (He had made a similar flight two weeks before but his crew hadn't reported it to anyone. In those days there was no air traffic control system as there is today and no way of tracking an aircraft's flightpath. He was flying with a different set of crewmembers on the fateful day.) The events of that day can only be explained by youthful exuberance and the desire to make an impression on the folks back home. He did, but not in the manner he had expected.

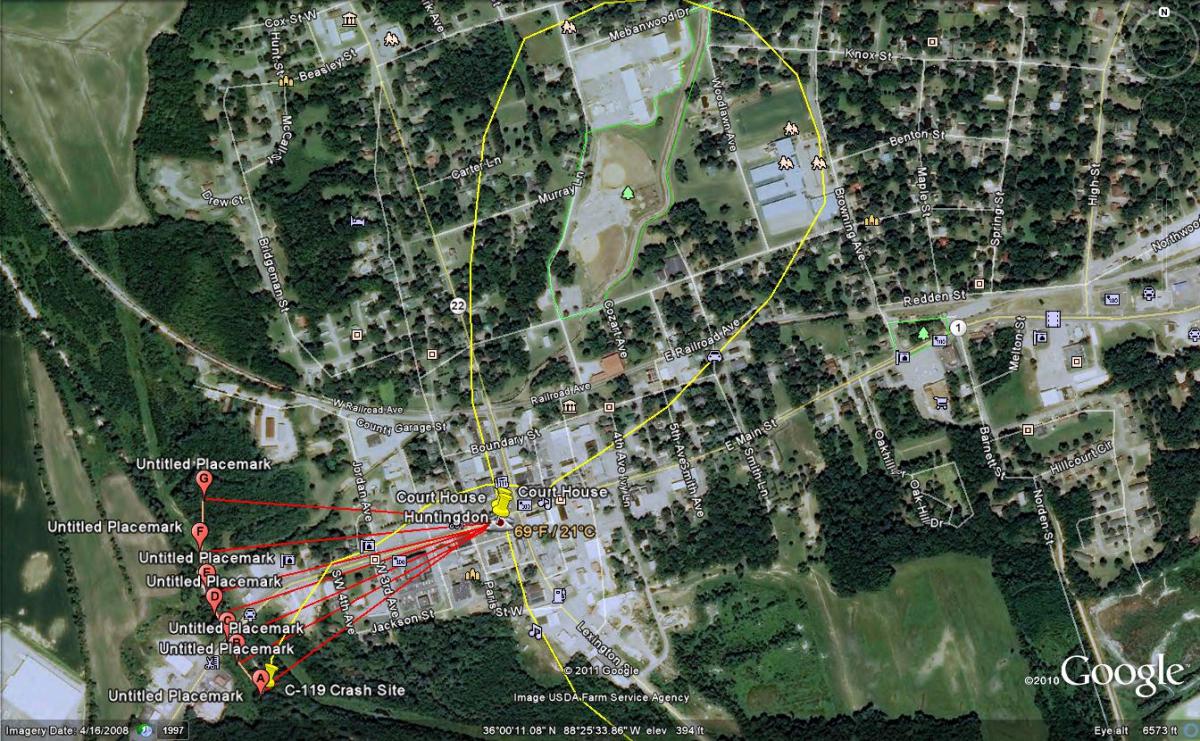

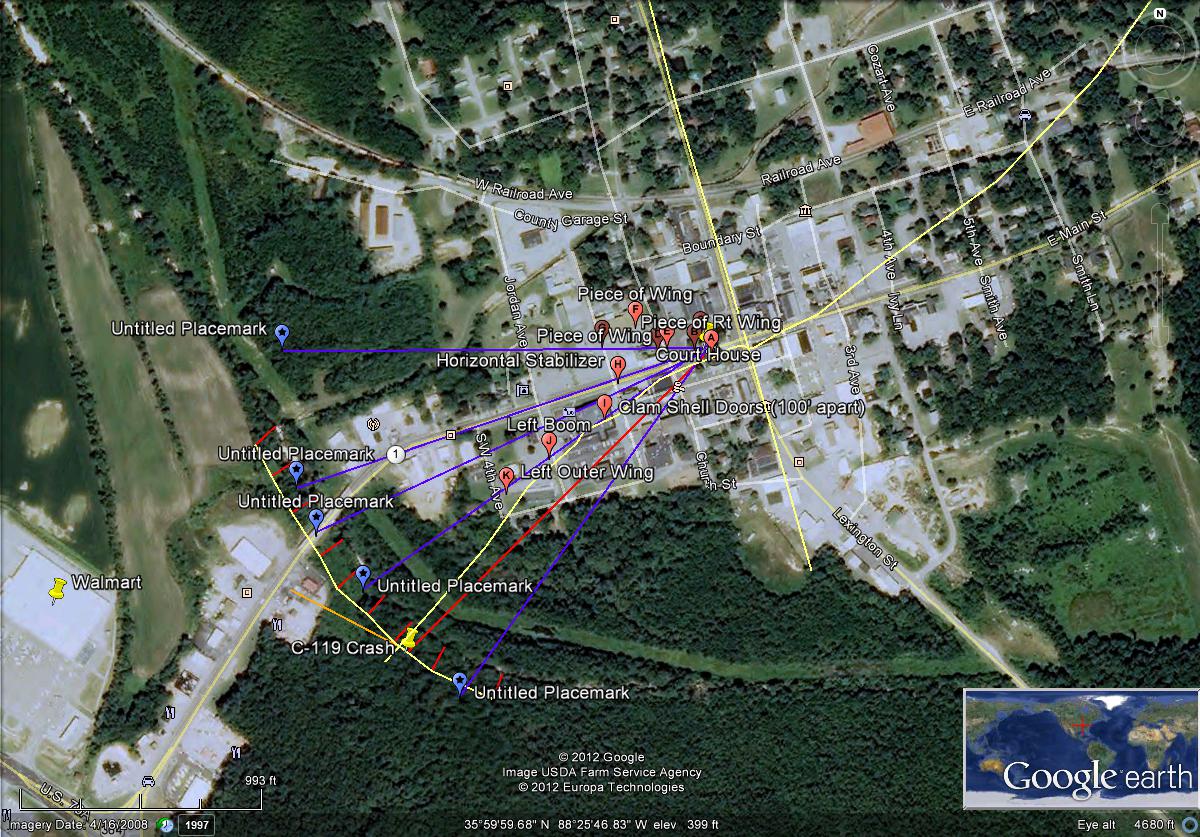

The

above diagram depicts the sequence of events as reported in the

statements of the witnessess - the yellow line depicts the airplane's

approximate path, although it may have actually been a bit more to the

south. The red lines and points sequenced A to G represent an arc 1,750

feet from the court house, the approximate distance the airplane

covered after it

started coming apart until it impacted the ground. (The distance is

approximate because the exact point at which the airplane began coming

apart is unknown. It was apparently believed to have been just east of

the courthouse since he was seen to initiate a steep pullup as he

approached the building.) Lt. Jenkins

approached Court Square from

the south and passed over it at an altitude estimated to be 100-200'.

(One witness puts his path a block or two to the east, but its not

supported by other witnesses.) After passing over the courthouse, he

began a "tight" right hand 270-degree turn which brought him back

toward the courthouse on a generally

westerly heading. While making the turn, he evidently

deliberately

passed over or close to Huntingdon High School. One witness

reported that he was traveling from northeast to southwest as he came

over Court Square. A couple

said the airplane came over the Bank of Huntingdon. It is

difficult to pinpoint exactly where the

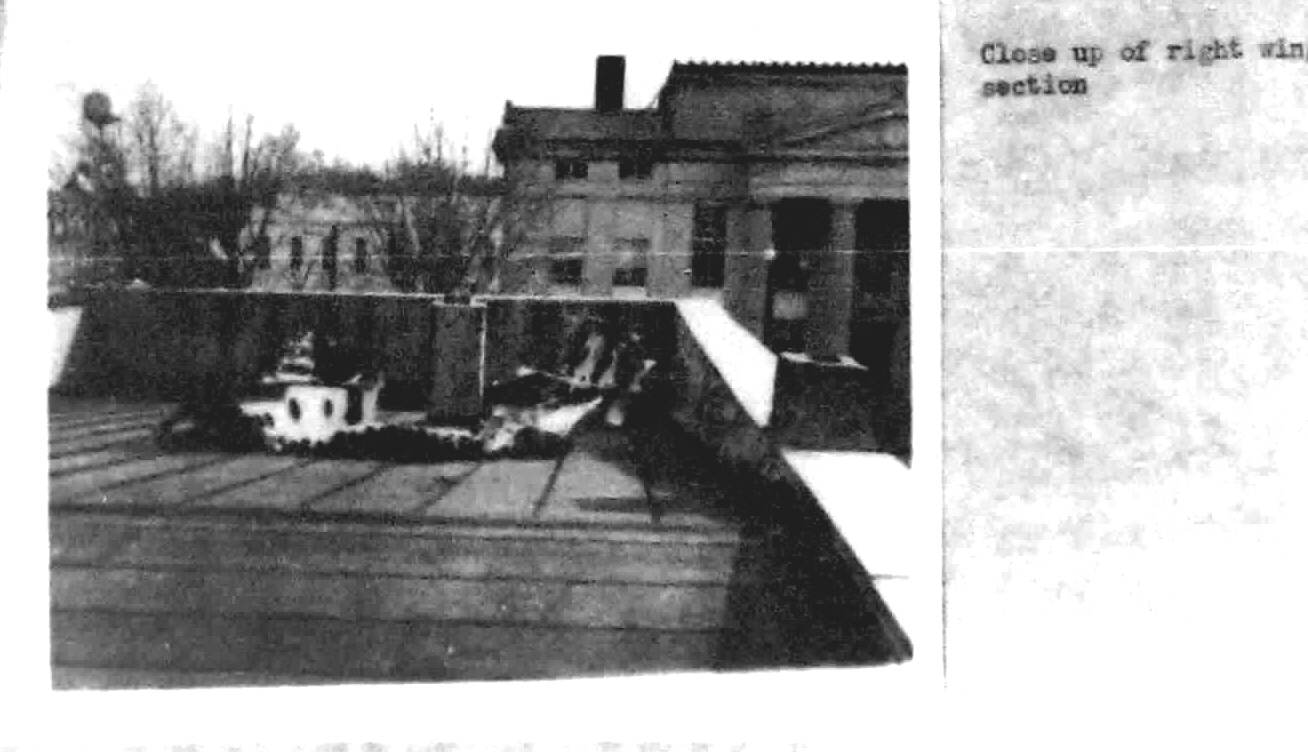

fuselage came over the courthouse although the location of a piece of

the outboard right wing on top of the building indicates the path was

somewhat to the south of the building. (C-119 wings were in two

sections, with the inner portion being from the fuselage to the boom

and the outer section outboard of the boom. See above photos.) The wing

span of a C-119 is 109

feet

and the courthouse is 110 feet long (southeast to northwest) and since

an aileron, which is at the end of the wing, landed on the courthouse

roof, the fuselage would have been south of the building. Each

witness saw

the events from a different angle. One, Royal Crider the post office

worker, said the

fuselage was over the street between the post office and the

courthouse. This would be commiserate with the location of the aileron

on top of the building. As he approached the courthouse -

the airplane

evidently

came over the bank on the opposite side of the street which would

indicate he was headed to the southwest - he began a

steep climbing turn to the right but, as soon as he did so, both wings

failed. A tearing of metal sound was heard by witnesses, followed by a

"whoosing" sound as high octane aviation gasoline, probably 115/145,

streamed out of the right wing and caught

fire, probably from contact with the engine exhaust. The airplane left

a trail of burning fuel along its flight path. Thr remaining fuel

exploded and caught fire right after the airplane impacted the ground

in a cornfield just outside the town. It is believed

that Lt. Jenkins applied full power as he started the pullup (he was

probably already at full power since he was estimated to be traveling

at

250 MPH) and that

the engines continued to run at full power all the way to the impact

point west of town. Photographs of the engine controls show the

throttles and propeller controls pushed all the way forward. The

accident investigation team determined that the

wings failed because Jenkins attemped to initiate a steep pullup

at a speed well in excess of the airplane's design limit manuevering

speed. The C-119C maneuvering speed is 187 MPH; Jenkins is believed to

have exceeded that speed by as much as 60 MPH. In short, he literally

pulled the wings off the airplane when he tried to make a sudden steep

climb. Some witnesses believed he was so low that he pulled up to avoid

hitting the building. After the wings failed, pieces of

the airplane kept

falling off along a path 1,200' long and 600' wide - the final accident

report says the stream of debris was 1,700' long. The right wing failed

in three places and the first pieces were found on top of the

courthouse. Other pieces were found on the courthouse lawn and in the

street. One piece fell on the roof of The Tea Room, a restaurant on the

corner of Main and Court Square. Some pieces were just north of

Main Street/US 70. All of those

pieces were from the airplane's right wing, which indicates the actual

path was further to the south, especially since there was a "strong"

crosswind from the south. (The actual wind velocity is unknown - the 8

MPH from the southeast given in the accident report is from Jackson,

the nearest weather reporting station. Winds may have been stronger at

Huntingdon based on the reports of several witnesses that there was a

"strong crosswind.") The

horizontal stabilizer fell into the street 400 feet west of the

courthouse lawn and landed on top of

two trucks. The left boom fell off and came to rest 700 feet from the

courthouse. The outer section of the left wing, which failed and folded

backward along the left boom, was found 1,000

feet to the west. My recollection that there was an automobile

dealership in this vicinity at the time, possibly Priest Motors. Part

of the wreckage landed on the roof. (Some

local people, including school children who passed through on busses

later in the day,

believed they saw blood scattered all over this area. Since the

fuselage and cockpit was still intact at this point, there would have

been no blood; the crewmembers died on impact 750' further to the

southwest. They most

likely saw hydraulic fluid which streamed out when the left wing and

boom seperated. The Air Force used Mil 5606 hydraulic fliud, which is

bright red in color. There was a general state of hysteria and

confusion in Huntingdon after the crash, and except for a few men with

military aviation experience, few people realized what they were

seeing.)

Ernest Smith stated that when the boom came off,

the airplane "shunted,"

meaning it changed direction, and the boom "slipped off to the left."

This is consistent with a turn toward the left which took the remains

of the airplane to the point of impact. Burning gasoline fell on the

garden

where Mr. Homer DeMoss was working. He was burned so badly they had to

be hospitalized as was a young colored man working with him. The

flaming gasoline fell on a team of mules and wagon, setting the wagon

on fire and burning the mules. They had to be destroyed. Both wings,

the horizontal stabilizer

and the

left boom had come off of the airplane but even though the engines were

on fire, the fuselage and cockpit

remained intact along with the right boom until the airplane impacted

in a field 1,750' from where it began coming apart. The entire sequence

of events

occured in just a few seconds, probably no more than five. The USAF

investigators believed the

failing airplane inscribed a parabolic, an arc, meaning that it was

gaining altitude for about the first 1/2 of the flight, then started

losing it as it made its fiery

journey to where it came to earth. (It did not fall straight to earth

when the wings came off because of momentum. The inner wings were still

producing some lift but not enough to keep the remaining components

airborne. After the wings came off, the remnants became a projectile.)

However, T.W. Wood, who

was closest

to the impact point, reported that it maintained about the same

altitude until it was about 100 yards from where it finally struck the

ground. The airplane was diving at about a 60-degree angle at the time

of impact and both engines were running at full power, although the

right one was on fire. Accident investigators determined the power

turbines (turbochargers) were intact.

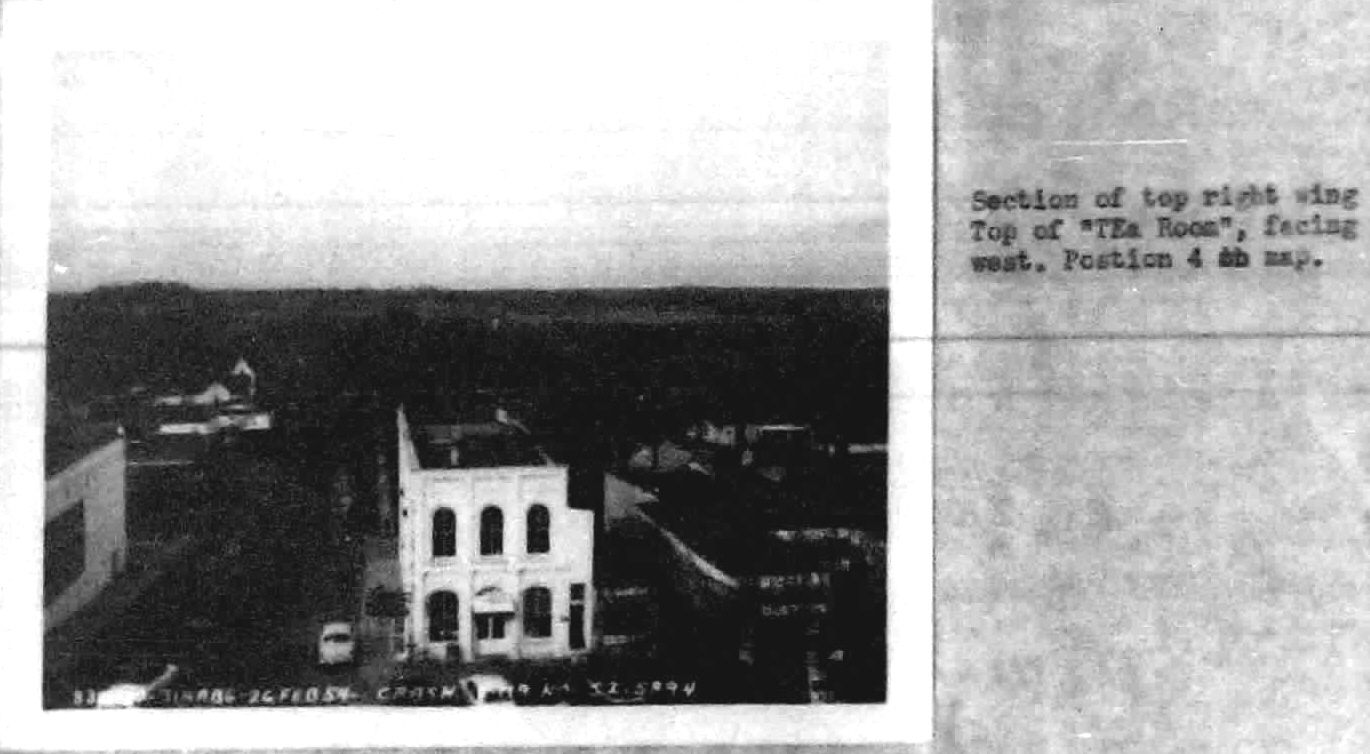

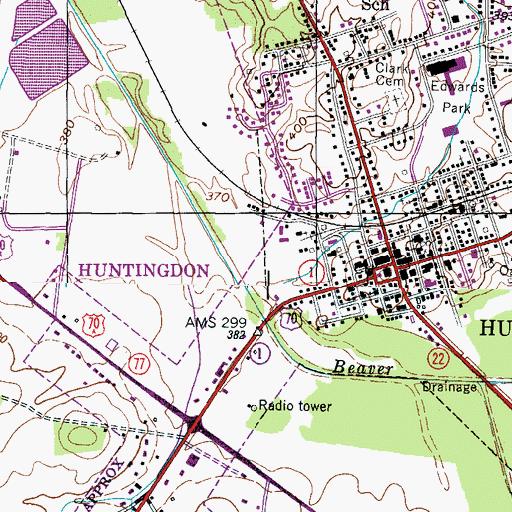

The above image depicts the most likely location of the

impact point based on the 1,750 foot measurement given in the accident

report. Due to Beaver Creek's northwest/southeast orientation, the

measurement does not allow for an impact point further north. For

instance, immediately north of the US 70/Main Street bridge 1,750 feet

would be right in the middle of the creek. Measurements of the initial

impact point from the creek bank place it at 110', with the debris field

extending to the left on an angle for approximately 300' to the southwest. Considering

the effect of momentum, the debris field extended along the aircraft's

line of flight at the time it impacted the ground.

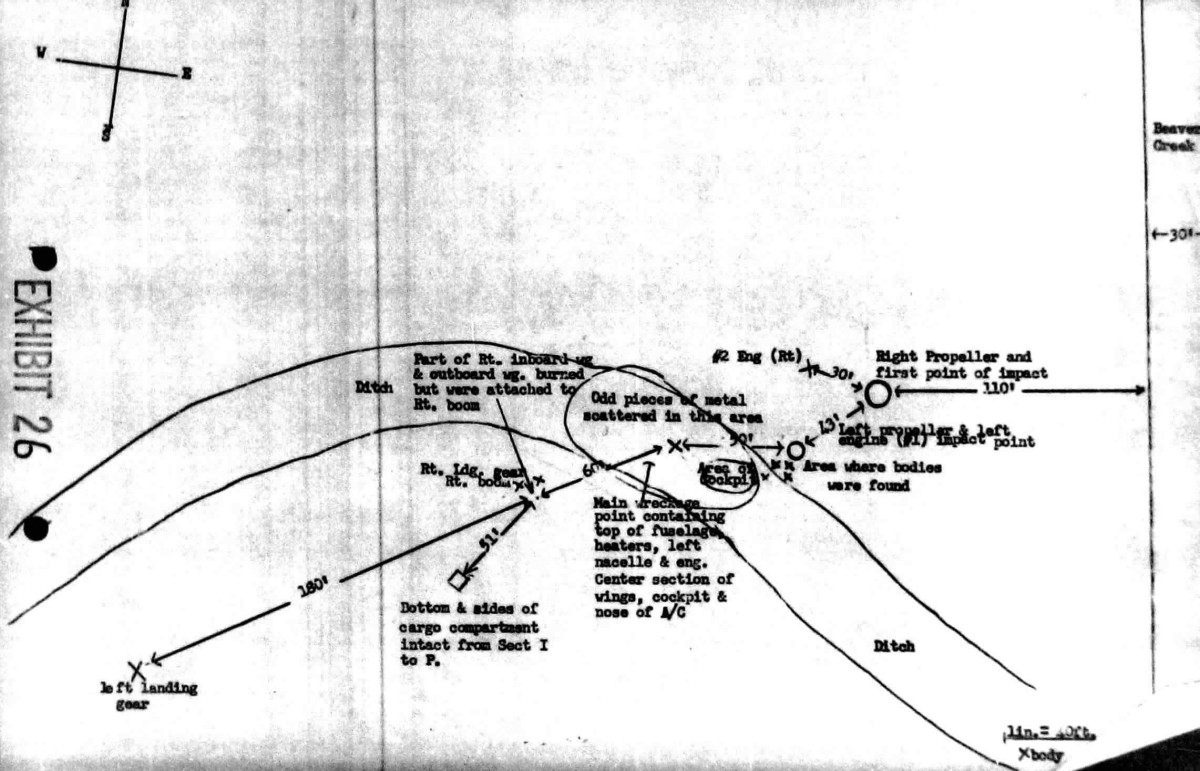

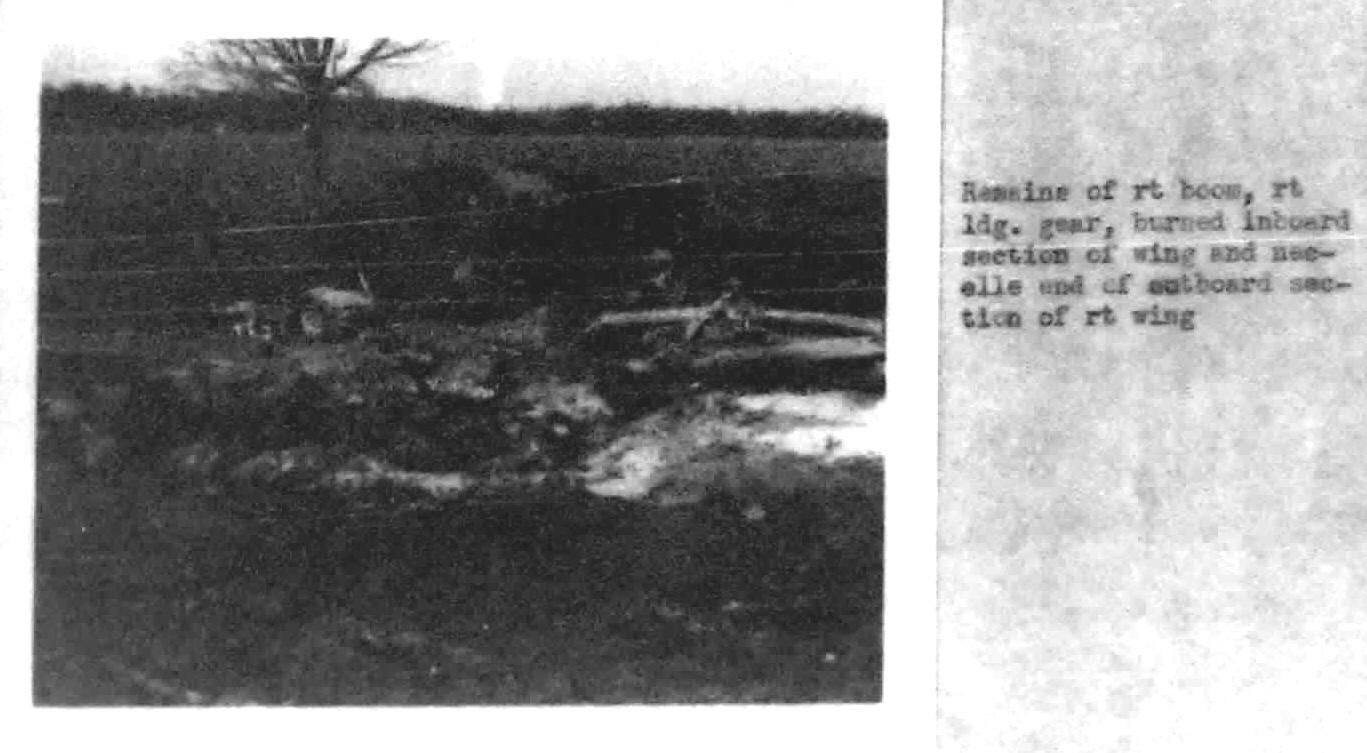

The above diagram shows the impact point at 110 feet from Beaver Creek, which runs in a northwesterly direction just to the west of Huntingdon. The bank of the creek is depicted on the right, with the impact point 110' from it in a straight line. After impact, the wreckage continued in a southwesterly direction. Three bodies were found at a point 43' from the point of initial impact and the fourth was in the ditch. The main wreckage rolled into a drainage ditch - the accident report relates that it was "nearly demolished." This ditch was deep enough that the cockpit and top of the fuselage are not visible in the photograph of the debris field. Parts of the airplane, including the bottom and sides of the cargo compartment, came to rest about 100 feet from the drainage ditch and 51 feet from where the right boom and part of the right wing came to rest. The left landing gear came to rest 240 feet from the center of the ditch. The total spread of the wreckage from the impact point is approximately 300-342 feet. (The

total shown in the diagram is 342 feet, but there is an angle involved.)

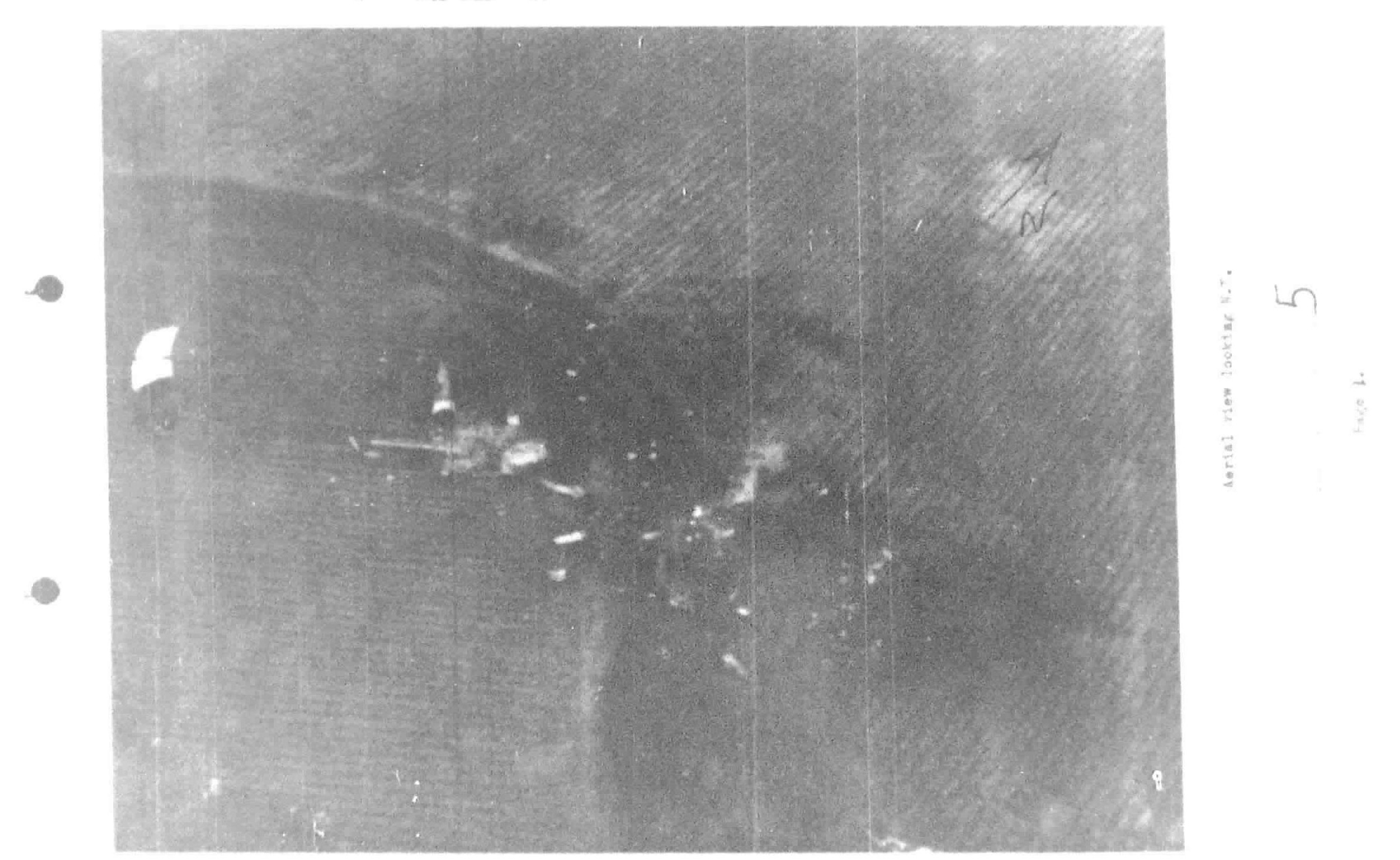

The above aerial photo shows the

wreckage along the drainage ditch. The lines in the

photograph are probably the remnants of corn rows from the previous

year's crop. Note that the debris field is spread along a

northeast/southwest line. This is an indication that the remains of the

airplane were headed southwest at the time of impact. The area of the

crash was allowed to grow up and is now covered by woods but the

outline of the ditch is visible in the Bing Maps image linked below.

(There appears to be a drainage ditch some 300 feet north of US 70 in recent satellite imagery but

it does not match the contour shown in the diagram and is some 2,000 feet from the courthouse. Furthermore, there

were several buildings along the northwest side of 70 at the time. No buildings are visible in the aerial photograph.)

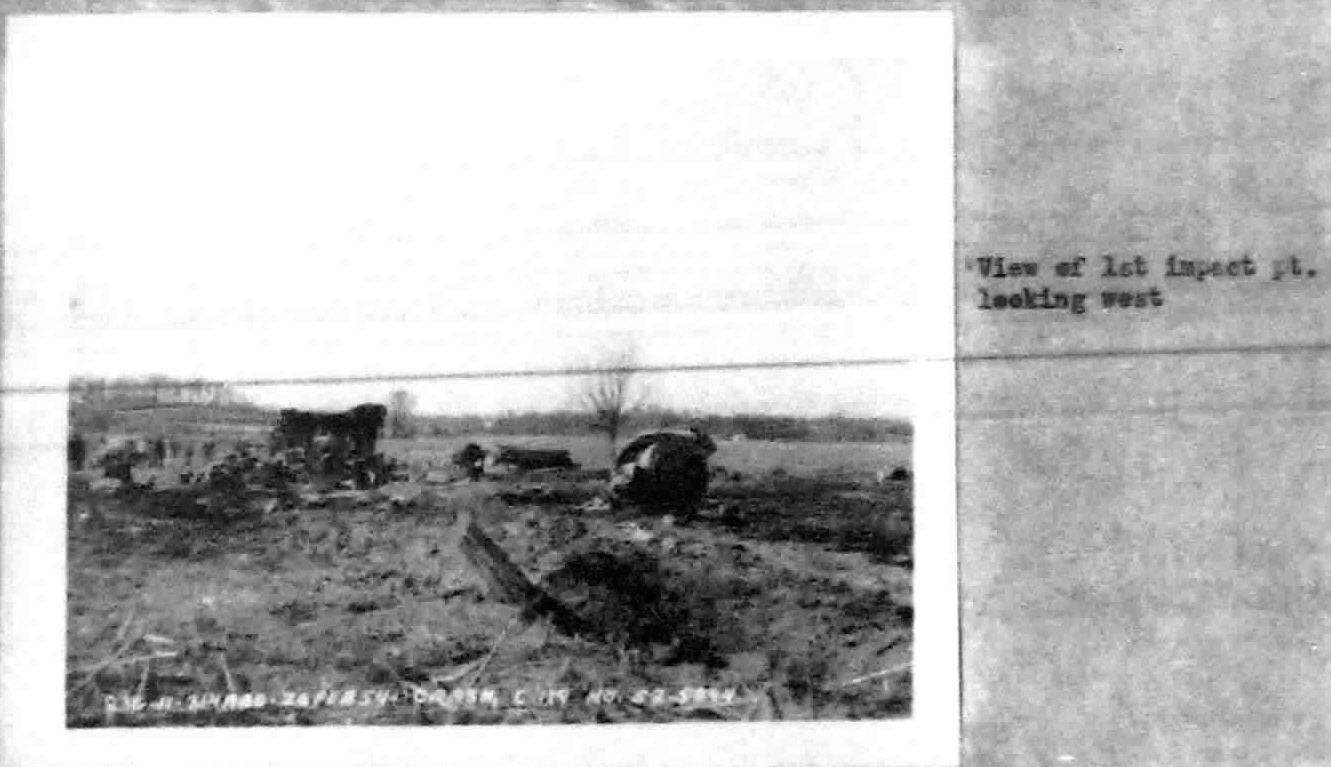

The

above photo is of the impact point looking in a westerly direction.

Note the higher terrain in the background at the edge of the bottom.

In 1954 Highway 77 around the west side of Huntingdon south of US 70

had yet to be built. The photographer was facing away from Beaver

Creek, which was right behind him, looking in a westerly direction. The object in the foreground is a

propeller blade - it dug into the ground. Immediately behind it is the

left engine nacelle. Note the small white building in the background to

the right of the nacelle. It's the service building for a radio tower

that was located in the field. It may not be there now. Due to the

distance from the camera and its small diameter, the tower itself isn't

visible.The larger

object to the left is part of the fuselage or cargo compartment. Note

the figures behind and to the left of it for perspective. The

photograph was no doubt taken with a wide angle lens. The debris field

is several hundred feet and the hills in the background are over a

quarter mile away.

Above is the Huntingdon segment of the Palmer Shelter topographic map of the area. (The Palmer Shelter map has since been redrawn and is less detailed. This one was downloaded in 2011-2012 and was dated in the 1990s.) Note the location of the radio tower. There was a small white building - small square adjacent to the circle representing the antenna - at the base. The circular area to the northwest of the intersection is the hill visible in the preceding photograph. Here is a link to the current map.

The

above photograph is of the area as it is today (April, 2008.) The large

building on the left is Walmart. Somewhere near Point A is the most logical place for

the impact point to have been - and is where I have always remembered

it as being. The

only place north of US 70 where it could possibly have

been would have been at Point D, but if the airplane impacted there,

some of the wreckage would have been in US 70 and the debris field

would have been strewn across it. T.W. Wood was working in

the field left of the bridge (North) at approximately 200 yards from it

(600') as reported in his statement. He saw the airplane from the time

it started coming apart over the courthouse until it crashed, but makes

no mention of the crash site being close to his immediate area. A plot

of the

position using a line 110' from Beaver Creek and 1,750 feet from the

courthouse places the impact point near the shown position. (Plotting

a position on a map is very simple - draw a line a specified

distance from a known reference line, in this case 110' from the

creek, then construct an arc using the known distance from another

known reference point, in this case 1,750' from the courthouse, and

where the two lines intersect is the point you're looking for - the impact point of the remainder of the C-119.) The plot

does not allow an impact point north of US 70 at all; the intersection

point is in the vicinity of Point A as shown on the map.

The above picture is of the plot of the crash site, using information from the accident report. The biege line represents a line running parallel to Beaver Creer. The blue vectors represent 1,750 feet from the courthouse, with the red line from the courthouse to the biege line intersecting with the parallel line. The crash site has to be at or near this point. The orange line is a direct line from US 70 to the crash point, a distance of just over 500 feet. This plot was made using a closer view of the crash site to make

the measurements from the creek

bed.

The

accident and the sight of the wreckage when I went up there the next

day with my family made an impression on me that has been with me for

all of my life. Every time I passed by the area on the way into

Huntingdon I thought about it. As it turns out, nine years later I

became a member of the 464th Troop Carrier Wing, the unit to which Lt.

Jenkins and his crew were assigned. I was not aware of this, however,

until I found some information on the Internet. I had always thought

the airplane was from Sewart AFB near Nashville. I also had thought

that the accident was caused by a stall, but it turns out it was

actually caused by structural failure. He was reportedly going around

250 MPH when he came over the courthouse on his last pass, far in

excess of the maximum manuevering speed (Va) at which a pilot can

safely

execute an abrupt maneuver. I did not understand what had actually

happened until I obtained a copy of the accident report.One of my

friends is a retired Air Force officer who was on the board. He told me

they foundt that the wings had failed before I decided to order a copy

of the report. The accident was a real

tragedy, and as it is with accidents, it didn't have

to happen.

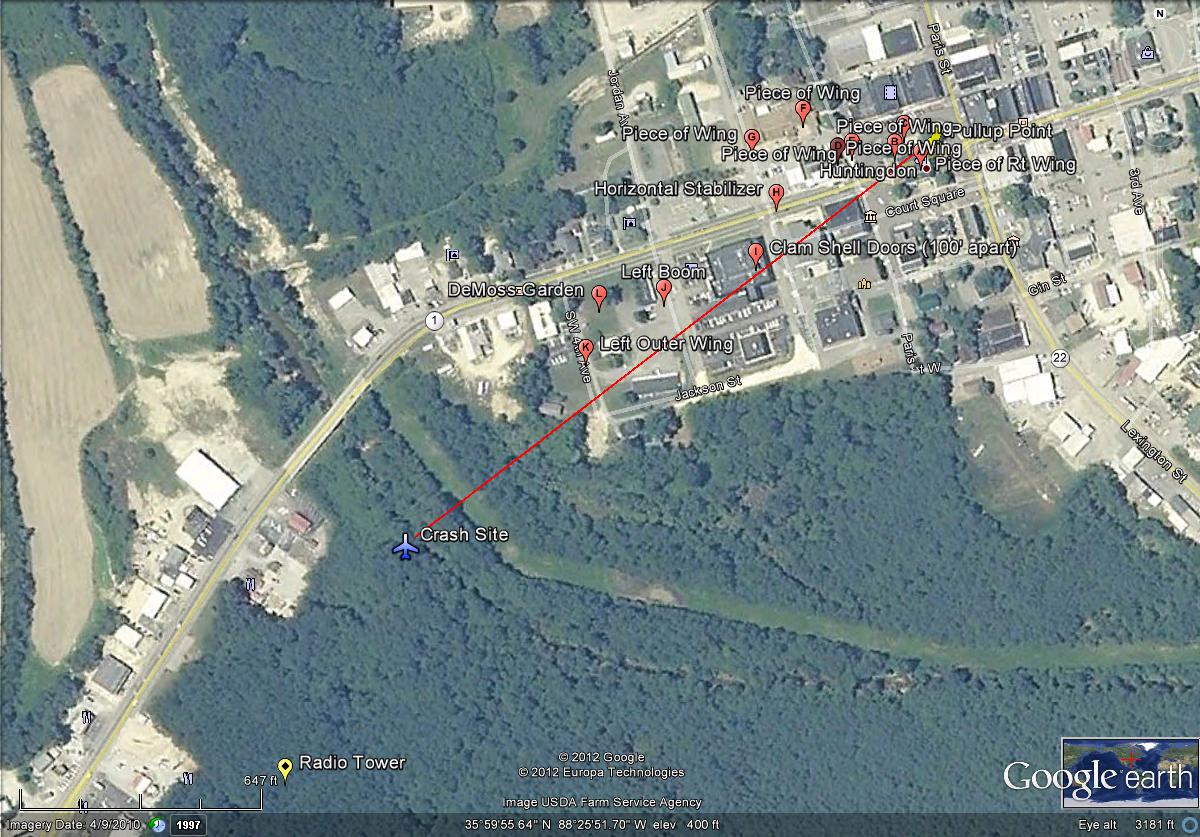

After considering the information regarding pieces of debris and where

they were found in relation to the courthouse, I realized it is

possible to determine the airplanes approximate path based on where

they were found and plotted them as shown above. Specific locations are

given for the pieces of wing found in the vicinity of the courthouse,

on top of the Colonial Tea Room and in the Electric Company parking lot

as well as the horizontal stabilizer, which landed on the street.

Distances are given for the clam shell doors, which fell 100' past the

horizontal stabilizer 100' apart, the left boom and the left outer wing

- which actually folded back along the boom when the airplane started

coming apart over the courthouse but didn't come disconnected from the

rest of the wing for at least another 1,000 feet. When considering

where the pieces fell, it is important to remember two things - that

all of the pieces around the courthouse, the Colonial Tea Room and

Carroll County Electric were from the right wing and that there was a

strong wind from the south which would have caused them to drift

north

of the actual flight path. A;though the actual wind at Huntingdon at

the time of the crash is unknown, winds at Jackson were out of the

south 8 MPH. However, witnesses reported that there was a "strong

crosswind" when Jenkins came over the courthouse. How far they drifted

would depend on how

high the airplane was when they came off - at least one witness

estimated it reached 255 feet altitude. Because the pieces were

aluminum

and, in the case of the horizontal stabilizer was an air foil, they

would not fall straight to earth but would come down in an erratic

manner like a falling leaf and drifting to the north as they

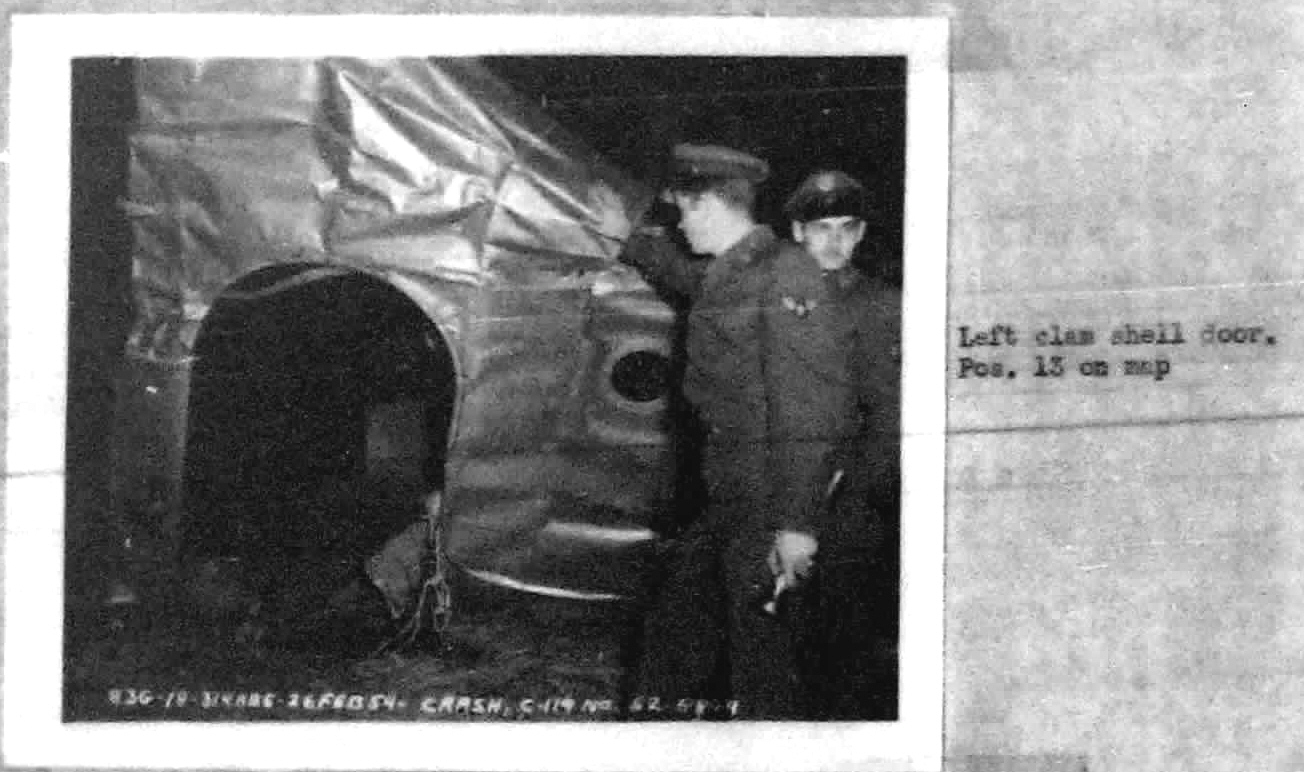

fell. The clam shell doors were large pieces made

primarily of aluminum and would have floated down in the same manner.

The pieces are

identified by red markers marked in sequence A to K. The debris field

was 600' wide and 1,700 feet long.

There seem to have been a lot of rumors that were spread after the

crash. One is that Jenkins had told people that he was going to "take

the flag off of the courthouse." The intial report was that the

airplane struck a flag pole, but it turned out to be in error. For that

matter, it is questionable that there was a flag pole on top of the

courthouse in 1954. It's not there now but is on the grounds on the

west side of the building. (Regarding directions, the courthouse

actually is constructed on a northwest-southeast line. There is also a

significant magnetic variation in West Tennessee, meaning that West on

a compass is actually about 267 degrees in relation to True North.) All

of the witnesses

interviewed by Air Force investigators agreed that the airplane didn't

strike anything before it started coming apart. Another rumor is that

Jenkins was actually standing in the back of the airplane when it came

over Huntingdon. Well, considering that the C-119G is equipped with

large clamshell doors at the back of the cargo compartment, how anyone

on the ground could see someone standing in the back is beyond my

comprehension, unless a paratroop door had been removed . Even if one

or the other of the paratroop doors was

open, it's unlikely that any of the crewmembers were in the rear since

they all had seats in the cockpit. It is possible that the crew in the

cockpit might have

been visible, especially when the airplane was in a bank. There is no

doubt that the clamshell doors were

installed because they were found on the ground in the debris field.

C-119s were flown without the clamshell doors on airdrop missions and

its possible they weren't installed on the first flight, but unlikely

since it was February, he was not on an airdrop mission and he flew

over 300 miles to reach

Huntingdon. Then there is the question of why Jenkins would have left

the cockpit to go to the back of the airplane and leave an

inexperienced copilot to fly the airplane while performing a classic

buzz job! People who knew him have said that Jenkins was a

"daredevil" which may very well be true but Air Force investigators

reported that he hadn't exhibited any reckless behavior. In fact, one

of his supervisors said that Jenkins was the last man in the squadron

he'd have suspected of buzzing. One witness,

who had served as an intelligence officer in an Army Air Forces combat

unit in World War II, and knew him well, described him as a quiet and

well-mannered young

man. Some have also

said that he

was taken out of fighters and put into transports but his record

doesn't indicate this. His record indicates that he completed Air Force

pilot training and was commissioned in June, 1952 and went almost

immediately to Japan to

his first assignment with the 314th Troop Carrier Group. He returned to

the United States a year later and was assigned to the 777th Troop

Carrier Squadron in August 1953. It is very

possible that his recklessness had been suppressed prior to his upgrade

to first pilot because he had always flown as a copilot and was under

another pilot's supervision. Another rumor is that he was engaged to a

girl who was still going to high school, which I find a bit hard to

swallow since he was 24 years old and had been out of high school for

almost seven years. One witness mentioned that he was engaged to one

of the girls' at the high school's older sister, which is more likely.

Some believed he flew

over the school to impress a girl, but while he no doubt intended to

fly over or close to the school, it would have been hard for an

airplane that size to make a circle to the east and not pass over it.

He was supposed to have flown over the school at that particular

time because he knew the girl would be outside in some kind of sports

or cheerleading practice - but the accident occured in February. The

temperature that day was in the 50s. In fact, his arrival over

Huntingdon at that particular time is more likely due to his time of

takeoff from Lawson Field. A newspaper account was published right

after the crash that stated

that the airplane hit a house after passing over the courthouse. This

report turned out to be false, however. It also stated that it sheared

off a flag pole, but this report was also untrue according to the

witnesses interviewed by USAF flight safety investigators the following

day. There is another question - a number of men claimed they went to

the site and helped pull the bodies out of the airplane but the police

chief witnessed the crash from a quarter mile away and was one of the

first people there. He states that he took immediate action to secure

the area and keep people away from the site until Air Force personnel

could arrive to begin their investigation. (The accident report

indicates that the bodies were thrown out of the airplane when the

cockpit was demolished during the impact and subsequent tumbling. The

police chief said he and his fellow law enforcement officers covered

them with parachutes and left them until military authorities in the

form of local National Guard personnel, arrived to take possession of

them. With Air Force approval, the bodies were removed and taken to a

local funeral home.)

It's important to understand how aircraft accident investigations are

conducted. First, all wreckage must be secured by law enforcement to

prevent people from looting and to insure that the wreckage remains

where it fell until investigators can make note of the position.

Precise measurements are taken using surveying equipment and placed

onto a diagram and/or map. In this case, the accident report refers to

a map of the debris and positions of the witnesses but it was not

included in the packet I received

from the people who obtained the report from the Air Force and offered

it for sale. Statements are taken from witnesses to the accident,

including from crew and passengers if there are survivors. In the case

of the Huntingdon crash, a number of statements were taken, with the

majority from men with military aviation experience. All were

from men who actually saw the airplane start coming apart over the

courthouse and/or saw the final impact. Also, it is important to

understand that the sole purpose

of the investigation is to determine what happened and why in order to

prevent future occurences. In this case, the intent of the accident

investigation was

to determine what caused it, which turned out to be structural failure

due to the pilot exceeding published airspeed limitations. All

available pieces of wreckage were

retrieved by Air Force personnel from Sewart AFB, Tennessee at Smyrna,

and taken there and reassembled so they could be studied by experts

including aeronautical engineers. Military accident reports are

classified as "Special Handling Required" and are not released to the

general public. Once the investigation has been completed, the report

is disseminated to the various military organizations "with a need to

know." However, in the 1960s the Department of Defense allowed

the public release of accident reports through 1955. Accident reports

since then may be obtained by filing a Freedom of Information request.

They are copied on to microfilm and stored at the Office

When I first read the accident report and since, I wondered why Jenkins would have initiated a turn to the right when he would have been in the left seat of the airplane - he was the aircraft commander or first pilot whose seat is always the left seat. After re-reading the report numerous times, I realize that he may not have. According to witnesses and the location of the pieces of the right wing, the first part of the airplane to fail, he started a pullup and the airplane started coming apart just as he came over the courthouse. That a piece of the wing fell on the courthouse roof is an indication that he started the pullup and the airplane started coming apart before he was over it. Bear in mind that the pieces were traveling at the same speed as the airplane when they came off of it and fell in a parabolic, with drift caused by the crosswind. There is no doubt that the airplane banked to the right as it climbed but this may have been due to the sudden decrease in lift as the right wing failed. Some witnesses indicated that he was on a westerly heading but one said his heading was more southwesterly, which is consistent with the airplane having passed over the bank then over the south end of the courthouse. Since there was a south wind - winds at Jackson were reported at 8 MPH out of the southeast - the falling pieces would have drifted to the north of the airplane's actual path. That one part fell on the Tea Room is an indication that the flight path was south of Main Street since the Tea Room is on the north corner of Main and Courtsquare. The pieces that fell the furtherest north fell on the electric company but they were parts of the wing and would have been more affected by the wind than a more solid object would have been because it would have taken them longer to fall (they would have been falling like a leaf, not a rock.) Royal Crider, who worked in the post office, stated that he was standing behind the building and witnessed the airplane from the time it appeared over the street south of the courthouse until it went into the field west of town. The accident report states that the airplane went west on a heading of 270 degrees but a heading and the actual relationship to True North are not the same. Compass headings are based on magnetic north while True North is based on the North Pole and there was considerable magnetic variation in West Tennessee in 1954 as this map shows. This is important because maps are based on True North. The line of zero declination has shifted several hundred miles to the west since 1954. Today's declination for McKellar Field is 1 degree west but in 1954 it was at least 3 degrees west. In fact, the sliding scale indicates that in 1954 the declination in West Tennessee may have been as much as five degrees. This would mean that magnetic north, the reading from a compass, could have actually been 265 degrees True. (To determine True North, the magnetic variation is either added or subtracted from the magnetic heading, in this case 270 degrees with westerly variation added. There is a common saying "East is least and West is best," meaning easterly variation is subtracted and westerly is added to the magnetic heading.) Since the variation was around 5 degrees in 1954, the True couse would have been 5 degrees less than the compass heading. Ernest Smith also reported that the airplane "shunted" when the left wing and boom came off, which indicates a change

of Air Force

Safety.

While I have a vivid memory of seeing the wreckage, I don't recall exactly how or when my family learned of the crash. My dad was an Army Air Forces aerial engineer in World War II and we were a very air-minded family so it was natural that we'd be interested. This was in the days before our family had a television and we often had the radio on and tuned to a local station in either Huntingdon or McKenzie. I believe we had recently had a telephone installed and someone - probably my Uncle Larry McGowan - may have called and told us about it. There was an article in the Memphis Commerical Appeal, to which we subscribed and recieved by mail, the next morning. (The article was erroneous in that it claimed Jenkins had hit a house.) I know that I went to Huntingdon the following day, most likely with Uncle Larry. My recollection is that he came by and picked up Daddy and me and possibly my sister to go to Huntingdon to see the crash site. (I to this day wonder why Daddy wanted to see the crash site. He had seen a number of crashes when he was in England during the war. Perhaps he wanted me to see it so I'd think twice about learning to fly. Even though I was only 8 1/2, I had already developed a very strong interest in aviation and was planning to learn to fly when I grew up - I did, my entire adult life prior to retirement was spent around airplanes.) My view was from US 70 looking at the wreckage from the north, as confirmed by the diagram in the accident report since I saw the section of main landing gear, which went the furtherest from the point of impact in a southeasterly direction. What I most recall is seeing the field of wreckage, with a wheel and tire lying flat and thinking about how a large airplane could be reduced to pieces. That image has remained forever in my mind. I also seem to recall an open parachute amongst the debris. The police chief said in his statement that they covered the bodies with parachutes. I don't recall seeing the demolished cockpit, which was lying in the drainage ditch. I also know that every time after that whenever our family had occasion to go to or through Huntingdon I would look over at the field and see it littered with the wreckage. I would also notice the Demoss House. Some how, I got the impression the pilot was Demoss' son and didn't learn otherwise for many years. There is one thing for certain - seeing the many pieces of

in direction. He indicates the shunt was to the airplane's left,

or to the south or southwest.

what had once been a large, powerful airplane made an

impression on me that I have carried ever since.

Return to Home Page

Links and Sources:

C-119 Page - Nothing specific to the Huntingdon crash, but a good source to learn more about the airplanes and their mission.

Bing Birdseye Map

of area as it is today.

Published September 23, 2011

Updated July 2, 2012

Last update September 19, 2017