WASPS, AIR WACS AND FLIGHT NURSES

In the mid-1970s, after the conclusion of the Vietnam War, the

United States Air Force began accepting young women as pilot trainees. The

destination for the women who successfully completed undergraduate pilot

training would be primarily into the Military Airlift Command, where they would

take their place in the cockpits of military transports and light utility jets.

The women who entered the world of military airlift were following in the

footsteps of another generation, the women pilots of the Womens Auxiliary

Ferrying Service and the Womens Airforce Service Pilots of World War II.

In the mid-1970s, after the conclusion of the Vietnam War, the

United States Air Force began accepting young women as pilot trainees. The

destination for the women who successfully completed undergraduate pilot

training would be primarily into the Military Airlift Command, where they would

take their place in the cockpits of military transports and light utility jets.

The women who entered the world of military airlift were following in the

footsteps of another generation, the women pilots of the Womens Auxiliary

Ferrying Service and the Womens Airforce Service Pilots of World War II.

The possibility of using women as Army pilots had been suggested

as early as 1930, when the War Department sent a query to the Air Corps

suggesting their possible use. The proposal was promptly rejected by the Chief

of the Air Corps, who replied that the possibility was "utterly unfeasible" due

to women being "too high strung for wartime flying." Ten years later, in 1940,

the Air Corps Plans Division proposed the use of approximately 100 women pilots

as copilots in transports and for ferrying single-engine airplanes. General

Henry H. Arnold, the Chief of the Air Corps, turned down the proposal on the

basis that it was unnecessary. Still, the idea would not go away as various

proposals for the use of women in military roles were presented to the US

government from outside the Air Corps, and often from outside the military. In

1939 noted aviatrix Jacqueline Cochran wrote a letter to the wife of the

president, Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, suggesting the need for the planning of the

use of female fliers in a national emergency. Cochran advocated that the use of women

in auxiliary roles would free male pilots for combat duties.

In 1940, before the United States went to war, the

Army Air Corps established the Ferrying Command, an organization

responsible for flying US-built airplanes to points where they could be

delivered to ferry pilots from the countries who were allied against

the Axis powers in Europe. Initially, the Ferrying Command depended

upon the Air Corps Combat Command combat squadrons for the pilots to

make the flights, on the basis that the long cross country flights from

the American West Coast to the East Coast and Canada provided valuable

training experience that the crews could take back with them to their

squadrons. But when Pearl Harbor plunged America into the war, the

combat pilots were needed to staff the under-strength fighter, bomber

and troop carrier squadrons which would fight the war so the Army

contracted with the national airlines and other civilian aviation companies to take over some of the ferrying

duties. In mid-1942 Ferrying Command became the Air Transport Command,

with the ferry mission placed under the Ferrying Division, commanded by

Colonel William H. Tunner. In June, 1940 the Ferrying Command had been

authorized to employ civilian pilots with significant flight

experience, but the practice was still untried when America went to

war. Right after Pearl Harbor the Army began recruiting civilian

pilots, and by the end of January, 1942 343 civilian pilots with

backgrounds in non-airline civil aviation had been assigned to ACFC's

Domestic Wing. The men, all of whom had a minimum of 500 hours of

civilian flight time, were employed on a 90-day temporary basis. If

found qualified to fly military aircraft at the end of the probationary

period, the men were offered commissions as service pilots, a

qualification somewhat lower than that required for combat pilots. The

amount of flight time required was lowered to as low as 200 hours for a

brief time, but by 1944 had been increased to 1,000 hours.

In 1940, before the United States went to war, the

Army Air Corps established the Ferrying Command, an organization

responsible for flying US-built airplanes to points where they could be

delivered to ferry pilots from the countries who were allied against

the Axis powers in Europe. Initially, the Ferrying Command depended

upon the Air Corps Combat Command combat squadrons for the pilots to

make the flights, on the basis that the long cross country flights from

the American West Coast to the East Coast and Canada provided valuable

training experience that the crews could take back with them to their

squadrons. But when Pearl Harbor plunged America into the war, the

combat pilots were needed to staff the under-strength fighter, bomber

and troop carrier squadrons which would fight the war so the Army

contracted with the national airlines and other civilian aviation companies to take over some of the ferrying

duties. In mid-1942 Ferrying Command became the Air Transport Command,

with the ferry mission placed under the Ferrying Division, commanded by

Colonel William H. Tunner. In June, 1940 the Ferrying Command had been

authorized to employ civilian pilots with significant flight

experience, but the practice was still untried when America went to

war. Right after Pearl Harbor the Army began recruiting civilian

pilots, and by the end of January, 1942 343 civilian pilots with

backgrounds in non-airline civil aviation had been assigned to ACFC's

Domestic Wing. The men, all of whom had a minimum of 500 hours of

civilian flight time, were employed on a 90-day temporary basis. If

found qualified to fly military aircraft at the end of the probationary

period, the men were offered commissions as service pilots, a

qualification somewhat lower than that required for combat pilots. The

amount of flight time required was lowered to as low as 200 hours for a

brief time, but by 1944 had been increased to 1,000 hours.

The need for civilian trained pilots was

within the Air Transport Command, and particularly within its Ferrying

Division. Mrs. Nancy Love, an experienced pilot herself, was employed

with the Ferrying Division of the ATC in a non-flying position. As the

supply of experienced male pilots dwindled, Love proposed the

recruitment of the most qualified women pilots in the nation to assist

the ATC' s Ferrying Command as civilian employees. Love's proposal was adopted in the

summer of 1942 and 25 female pilots were recruited to become members of

the WAFS, with Nancy Love as commander. Each of the women had more than

1,000 hours of flying time and they quickly proved capable of the kind

of duties for which they had been envisioned. Originally assigned to

fly single-engine light airplanes, the women demonstrated that they

could

handle fast pursuit ships as well as four-engine bombers on

transcontinental ferry flights. In July, 1944 303 women pilots

were on duty with Ferrying Division, the most ever assigned, but the numbers dropped o to an

average of 140 as women with less experience and those lacking in

competency were transferred to the Training Command for other duties as

the demand for light trainers decreased and fighters became the primary

airplanes to be delivered.

While Love's pilots were highly experienced

aviators, Jackie Cochran had another idea in mind. Using her influence

with Eleanor Roosevelt, Cochran convinced the War Department to create

the Womens Flying Training Detachment, a program to train young women

with limited flying experience as pilots, with Cochran as director of

the program. Essentially, the mission of Cochran's program was to turn

out female pilots with the experience necessary for a commercial

pilot's license. Consequently, the

military found itself with two programs using female pilots, one a

valuable asset that took advantage of the skills of experienced women

who could make a significant contribution from the outset and the other

a politically motivated program requiring extensive training before the women could be productive. General

Arnold called a meeting of officials from ATC and Cochran and told them

there was not room for two programs - they would have to get together.

Cochran's political connections allowed her to prevail and her plan was

adopted. Cochran also used her political influence to gain command of

the program. On August 5, 1943 the WAFS and WFTD were merged to become

the Women Airforce Service Pilots, or WASP, with Cochran as Director of

Women Pilots. Nancy Love was made WASP executive officer with the

Ferrying Division of the ATC. The WASP program was not a military

program but was rather an auxilary and the women had no military

status. They were civilian employees of the Army Air Forces. No

comparable program was set up to train male pilots for civilian

employment.

| Cochran and Love |

The

two principles in the establishment of the women's flying program were

Jackie Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love, two accomplished female

aviators whose lives

and personalities could not have been more different. Love grew up

in Michigan as a doctor's daughter then attended Vasser College.

She learned to fly at age sixteen and wanted to be involved in

aviation. After graduating from college she married Robert Love, who

held a commission in the Army Reserve, and the two of them opened their

own aviation business in Boston in which Nancy worked as a flight instructor

and charter pilot. She also did some work for the Department of

Commerce and was an accomplished test pilot. Before the Lend-Lease Act

was adopted, US pilots weren't allowed to make deliveries to warring

nations, including Canada. The aircraft manufacturers contracted with

US civilian pilots to fly their products to airfields on the Canadian

border, where the airplanes were towed across the border. Nancy Love

flew several flights as a contract pilot. The

two principles in the establishment of the women's flying program were

Jackie Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love, two accomplished female

aviators whose lives

and personalities could not have been more different. Love grew up

in Michigan as a doctor's daughter then attended Vasser College.

She learned to fly at age sixteen and wanted to be involved in

aviation. After graduating from college she married Robert Love, who

held a commission in the Army Reserve, and the two of them opened their

own aviation business in Boston in which Nancy worked as a flight instructor

and charter pilot. She also did some work for the Department of

Commerce and was an accomplished test pilot. Before the Lend-Lease Act

was adopted, US pilots weren't allowed to make deliveries to warring

nations, including Canada. The aircraft manufacturers contracted with

US civilian pilots to fly their products to airfields on the Canadian

border, where the airplanes were towed across the border. Nancy Love

flew several flights as a contract pilot.

Cochran was also an accomplished pilot, but her accomplishments, like

those of Amelia Earhart, had been purchased using her husband's assets

and connections. An ambitious and power-hungry woman, who could also be

called "conniving," she seemed most interested in self-promotion and power. Jackie Cochran wasn't even her real name. Her real

name was Bessie Lee Pittman and she had been raised as a sawmill

worker's daughter in Lower Alabama and the Florida Panhandle. Cochran

was the name of the young US Navy enlisted man, an aircraft mechanic,

she married as a teenager as a means of getting away from home. She

concealed her true identity for all of her life. Although some of her

relatives lived with her in California, she claimed they were employees

and her "adopted family." After her divorce, she left the South

for New York City where she used her good looks to land a job as a

countergirl at Saks Fifth Avenue. While working at Saks she met and

seduced Floyd Odlum, a wealthy financier, who was married at the time.

Odlum left his wife and married Pittman, who had kept her married name

of Cochran, but had started calling herself "Jackie." She convinced

Odlum to finance her in the cosmetics business and buy an airplane

to travel around the country. Eager to make a name for herself, she

began competing in air races. concealed her true identity for all of her life. Although some of her

relatives lived with her in California, she claimed they were employees

and her "adopted family." After her divorce, she left the South

for New York City where she used her good looks to land a job as a

countergirl at Saks Fifth Avenue. While working at Saks she met and

seduced Floyd Odlum, a wealthy financier, who was married at the time.

Odlum left his wife and married Pittman, who had kept her married name

of Cochran, but had started calling herself "Jackie." She convinced

Odlum to finance her in the cosmetics business and buy an airplane

to travel around the country. Eager to make a name for herself, she

began competing in air races.

While Love's idea was to make the most efficient use of the nation's

female pilots, Cochran wa seeking to further her own ambitions. Her

goal was to become head of a military corps of women pilots. She is

alleged to have extracted a promise from Air Corps Commander General

Henry H. Arnold that he would not utilize women in any way unless they

were commissioned as officers and that he would consult with her on any

actions involving female pilots. She went to England and joined the

British ferrying service, which employed women as well as men. When she

learned that Love had been

appointed to head a squadron staffed by female ferry pilots, she was

incensed. She left England immediately and proceeded to Washington

where she confronted Arnold in his office. Arnold pacified her by

setting up a women's training organization under her command. After a

year with two organizations, Cochran managed to gain control of all

female pilots employed directly by the Army. Nancy Love, who Cochran

evidently percieved as a threat, became her subordinate.

|

That women could supplement male pilots was apparent

in 1942-43, when the war was still going against the Allies and the War

Department believed there would be heavy casualties among the males pilots who

went to war. As some of the women demonstrated superior abilities,

General Arnold directed that training in heavier and more difficult airplanes be

initiated "to the maximum extent possible." In 1942 Arnold wrote that the Air

Force's objective was to replace as many male pilots in non-combat flying duty

with women as was feasible. Cochran's training program did not lack applicants.

Advertisements over-glamorized the program, leading to a flood of applicants as

more than 25,000 women applied for WASP training. Only 1,830 were admitted of

which 1,074 completed the training. The

training program began initially at Hughes Airport - now Houston Hobby - in Houston, Texas, but moved

to Sweetwater, Texas due to lack of facilities. In the first months of the

program, when training standards were relaxed, the wash-out rate among women was

26% but increased to 47% in 1944 when the lessened need for pilots allowed more

stringent requirements. Still, the comparison to men was favorable as the

washout rate for men went from less than 25% to more than 55% over the same

period.

|

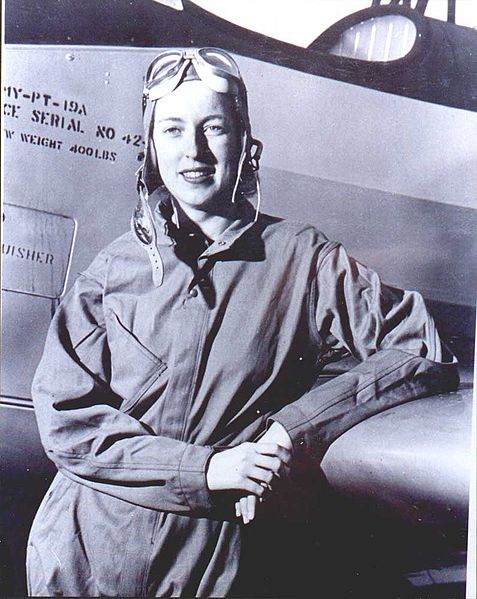

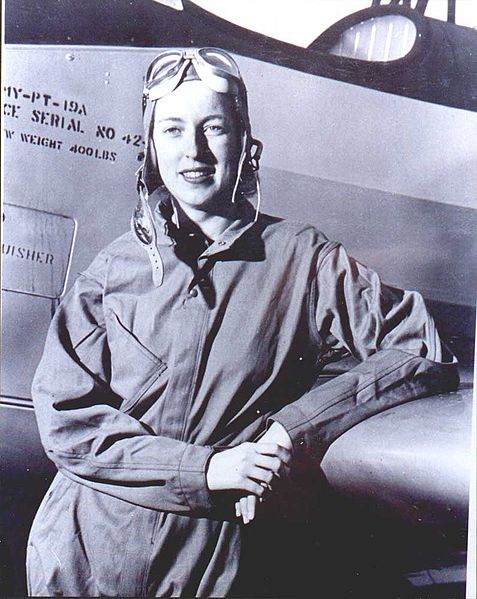

Cornelia Fort

The

second woman hired for the WAFS was Cornelia Fort, a Nashville

socialite who had already become a celebrity because of where she was

on December 7, 1941. (The first hired was Betty Gilles, whose husband

was an executive with Grumman Aircraft on Long Island.) After

graduating from college, she returned to

Nashville, where she learned to fly. She moved to Hawaii and

took a job as a flight instructor at Honolulu. On the morning of

December 7, she was in the air with a student pilot when the first

Japanese aircraft appeared in the skies over Oahu. As soon as she

realized the mysterious aircraft had hostile intentions, she returned

to land. A Japanese fighter strafed the airfield immediately after she

landed and killed her boss, Bob Tyce. The

second woman hired for the WAFS was Cornelia Fort, a Nashville

socialite who had already become a celebrity because of where she was

on December 7, 1941. (The first hired was Betty Gilles, whose husband

was an executive with Grumman Aircraft on Long Island.) After

graduating from college, she returned to

Nashville, where she learned to fly. She moved to Hawaii and

took a job as a flight instructor at Honolulu. On the morning of

December 7, she was in the air with a student pilot when the first

Japanese aircraft appeared in the skies over Oahu. As soon as she

realized the mysterious aircraft had hostile intentions, she returned

to land. A Japanese fighter strafed the airfield immediately after she

landed and killed her boss, Bob Tyce.

After

the outbreak of war, civilian flying in Hawaii was suspended so

Cornelia returned to the US where she did a war bond tour and made a

movie. Nancy Love contacted her in September, 1942 and offered her a

job with the WAFS and she immediately accepted. By March, 1943 she was

flying out of Long Beach, California ferrying Vultee BT-13 and Ryan PT-19 and PT-22 trainers. On

March 21 she was flying as part of a formation of BT-13s that were on

their way to Texas. The formation was mixed, with both male and women

pilots. Women writing about the WASPS have claimed that the male pilots

started teasing her, and began making simulated combat passes at her airplane but this

assertion is not borne out by eyewitness accounts. Evidently she and

another pilot, an Army flight officer, got too close and their

airplanes collided. Both crashed and both were killed. Cornelia Fort

thus became the first female pilot to die while in Army employ.

|

Initially,

the WAFS ferry pilots were assigned

primarily to the movement of light aircraft - trainers, liaison and

light utility transports. But as they proved their competence, some

women were allowed to move into more sophisticated airplanes. Betty

Gilles was the first WAFS pilot to check out on the P-47. The

Ferrying Division had an advancement policy that started out male

pilots in light airplanes them moved them into domestic ferrying of

four-engine bombers in preparation to their assignment to overseas

ferry and transport routes or to overseas duty with the Air Transport

Command, including on the perilous routes into China. The men were

brought into the Army as commissioned officers and flight officers and

designated as Service

Pilots on the basis of their civilian flying experience. The women were

civilians and had no military status; they were awarded no military

aviation badge. (Cochran designed wings for the women and had them made, but they were not Army badges.) As Civil

Service employees, the women were not subject to

overseas duty. Consequently, as the women gained experience, they

gradually moved into the domestic ferrying of fighters which, because

they were high-performance tailwheel aircraft (except for P-38s and

P-39s), were more difficult to handle than bombers, most of which were

equipped with tricycle landing gear. By the summer of 1944 the ferrying

of fighters had become the primary WASP activity within the Air

Transport Command. The

accident rate among pilots ferrying fighters, both male and female, was

much higher than with other types although only four women were killed

in fighters. In fact, all but nine were killed in trainers. This has

led to the myth that the

women were given more difficult assignments then the men with whom they

worked, which while partly true must be taken into context. Women were

ferrying fighters, not because they were more difficult to fly, but

because they did not fit into the training program for male military

pilots who

were destined for overseas duty and who were assigned to ferry

multiengine airplanes to gain experience before being assigned to

transport squadrons. Women in the Ferrying Division

received well-deserved praise from their superiors, including General

Arnold, who stated that commanding officers preferred WASP pilots to

deliver their airplanes because the women usually reached their

destination a day or two ahead of the men. This was because men tended

to stop off to see girlfriends while the women did not carry an address

book!

A widespread myth relates that female pilots

ferried half of the high-performance combat aircraft ferried within the

Continental US. Apparently started from an article written by a former

WASP about Nancy Love, such a number as reported is impossible. More than 60,000

fighters were produced in 1943 and 1944, the two years that the women

pilots were most active, and female pilots only ferried a total of

12,650 airplanes in their entire existence. If every single airplane

ferried by women had been a fighter, they would have only accounted for

20%! In reality, the majority of airplanes ferried by women were

trainers and light liaison aircraft. There was a period in mid-1944

when female pilots probably ferried around half of the fighters being

ferried at the time, but the assertion that they ferried over half of the fighters delivered in the US is an obvious myth.

Another myth that has been perpetrated in the

hyperbole related to the WASP is that they were engaged in a hazardous

occupation. In reality, their duties were routine. Ferry

missions consisted of picking an airplane up at the factory or a

maintenance depot and flying it to its operational base, or to a

modification depot. Some women were assigned to perform "test flights,"

but they were simply acceptance flights of brand new airplanes or

airplanes that had just come out of maintenance to insure that the systems worked properly. While pilots of tow

planes were towing targets that were being shot at by inexperienced

gunners, not a single female pilot was killed while towing targets.

Twenty-six of the women who died either died while in training or died

in trainer-type aircraft in accidents that today would be characterized

as "pilot error." No women were killed in light training aircraft such

as the Piper Cub which made up a large percentage of the aircraft they ferried. WASP hyperbole often claims that women performed

missions on a wide scale when they were really single-case incidents. A

WASP who was assigned to the research and development center at Wright

Field flew a Bell P-39 jet fighter. Another was picked for a special

project to fly a B-29 (with an all-male crew including an experienced

instructor pilot) around to training bases because of the

Superfortresses bad reputation. They were both isolated cases.

WASP

flying was exclusively within the United

States and occasionally into Canada. The director of Ferrying Division,

Brig. Gen. William H. Tunner, was impressed with the women under his

command

and sought to use them to the full extent of their abilities, including

on overseas ferry routes. In September, 1943 Nancy Love and Betty

Gilles,

two

of the most experienced female pilots assigned to ATC - Love founded

the WAFS and was director of women ferry pilots while Gilles was her

first recruit - were given a

mission to ferry a B-17 to England across the North Atlantic route. A

hand-picked crew - including Tunner's personal navigator - was

assigned to the mission to support the two women on what would have

been a history making event. The two female pilots set out from their

base at New Castle, Delaware in the B-17, expecting to take the Flying

Fortress all the way to Prestwick, Scotland. But when they got to

Newfoundland, Love and Gilles were ordered to surrender the airplane to

an all-male crew by personal order of General Arnold. Though Arnold

gave the order, just why he did so remains unclear since he had

previously given permission for the mission. Many of the former WAFS

pilots felt that Jackie Cochran put a halt to the mission because of

personal jealousy of Nancy Love's experience and notoriety within the

military. Cochran had flown her personal Lockheed Hudson to Scotland

earlier, and some women believed that she did not want to be

over-shadowed by Love. Others, those who came through Cochran's

training program, thought Arnold was afraid of the possible exposure of

the two women to interception by German fighters as they passed near

the Norweigan coast. (Such an explanation is very unlikely considering

that Norway is 500 miles east of the route from Iceland to the UK.)

Whatever the reason for the cancellation, the two

disappointed women returned to New Castle and no international ferry

flights were ever authorized for female pilots and crews.

WASP

flying was exclusively within the United

States and occasionally into Canada. The director of Ferrying Division,

Brig. Gen. William H. Tunner, was impressed with the women under his

command

and sought to use them to the full extent of their abilities, including

on overseas ferry routes. In September, 1943 Nancy Love and Betty

Gilles,

two

of the most experienced female pilots assigned to ATC - Love founded

the WAFS and was director of women ferry pilots while Gilles was her

first recruit - were given a

mission to ferry a B-17 to England across the North Atlantic route. A

hand-picked crew - including Tunner's personal navigator - was

assigned to the mission to support the two women on what would have

been a history making event. The two female pilots set out from their

base at New Castle, Delaware in the B-17, expecting to take the Flying

Fortress all the way to Prestwick, Scotland. But when they got to

Newfoundland, Love and Gilles were ordered to surrender the airplane to

an all-male crew by personal order of General Arnold. Though Arnold

gave the order, just why he did so remains unclear since he had

previously given permission for the mission. Many of the former WAFS

pilots felt that Jackie Cochran put a halt to the mission because of

personal jealousy of Nancy Love's experience and notoriety within the

military. Cochran had flown her personal Lockheed Hudson to Scotland

earlier, and some women believed that she did not want to be

over-shadowed by Love. Others, those who came through Cochran's

training program, thought Arnold was afraid of the possible exposure of

the two women to interception by German fighters as they passed near

the Norweigan coast. (Such an explanation is very unlikely considering

that Norway is 500 miles east of the route from Iceland to the UK.)

Whatever the reason for the cancellation, the two

disappointed women returned to New Castle and no international ferry

flights were ever authorized for female pilots and crews.

Undoubtedly, the glamorization of the WASP

was to a large extent responsible for their ultimate demise. The women

were civilians and thus denied the military status of

the male pilots who accepted military commissions as service

pilots. A bill was submitted in Congress in September, 1943 to

militarize the WASP but it failed to pass. Cochran and General Arnold

proposed the creation of a separate organization of female service

pilots headed by a woman with the rank of colonel, but the War

Department opposed such a move. No such organization existed for male service pilots. The USAAF felt that the women should be

commissioned in the Women Army Corps, an organization made up of women who were already members of the

military, many of whom were serving overseas in combat theaters and who

were authorized to fly in military airplanes including duty

as crewmembers. While Congress was still considering the bill, the

Civil Aeronautics Agency's War Training Service program came to an end

in January, 1944. College training programs and

civilian-contract flying schools were scheduled to close, thus freeing

large numbers of previously draft-exempt male flight instructors

for military duty. The grounding of so many well-qualified male pilots

and their possible reassignment to ground combat duties led to a

feeling of indignation against the women pilots who were seeking

military status. Simultaneously, as the war began to turn in the Allies

favor, large numbers of returning combat pilots were available for

ferrying, training and other duties then filled by WASP pilots. In

June, 1944 a Congressional committee on Civil Service matters decided

that the WASP program was unnecessary and unjustifiably expensive. The

committee recommended that the recruitment and training of

inexperienced women pilot trainees be halted but the women who were

already employed as pilots were also affected. The final class of female

pilots was allowed to graduate from Sweetwater on 20 December, 1944

but with their graduation the entire program was terminated.

In addition to their role with the Ferrying

Division, women were also used in Training Command and the domestic

numbered Air Forces. In the summer of 1943 some women were assigned to

target-towing duty training antiaircraft gunners. The women were judged

better in the mission than returning combat pilots (primarily due to

the ignorance of the women - the men had been shot at in earnest and

knew what flak was all about!) In I Troop Carrier Command some women

were assigned to fly tractors for glider practice. This was one area in

which women proved inequal to the task due to the physical strength

required to fly the Lockheed C-60s that were serving as tractors. Some

women were trained as instructors; while they were not assigned to

basic flight instruction, they served quite well in the instrument

phase of training. By the inactivation of the program, WASP pilots had

suffered 37 deaths, all to accident, while seven women received major

injuries and 29 others incurred minor injuries while on the job. One

other WASP pilot was killed in an aircraft accident while riding as a

passenger.

A footnote to the WASP story - As civilians,

the female pilots were not veterans and were thus not eligible for

benefits under the Military Readjustment Act. Of course, neither were

the civilian male pilots, including those who flew overseas flights, sometimes over hostile areas,

under military contract or with the airlines. In the 1960s as social

issues became prominent, the WASP caught the attention of feminists,

who began lobbying for veteran's status for the women. In 1977 they

were granted this status, even though none had flown overseas. It was a

status the more numerous male civilian pilots didn't even have! It wasn't until

1981 that male ferry pilots were recognized as veterans. Some airline

employees who flew overseas missions under Air Transport Command

contract weren't given veteran's status until the 1990s. The men - and

women - who worked in the civilian schools that provided primary and

other flight training have never been recognized as veterans.

While

the WASPS were in civilian status, large

numbers of women served with the US Army Air Forces in World War II

with full military status. The one group of women who shared the same

dangers as did male aircrew members were the female flight nurses who

flew with troop carrier squadrons in all of the combat theaters. For

the first year or so of the war, no medical personnel flew on air

evacuation missions, but the need was seen and a medical evacuation

training school was set up at Bowman Field, Kentucky. By

1944 more than 6,500 nurses were on duty with the USAAF, of which 500

were on flight status in the air evacuation role. Flight nurses were

selected from nurses on duty with the USAAF hospitals, and who recieved

the recommendation of the senior flight surgeon in their command. After

passing a flight physical, the women were sent to the School of Air

Evacuation at Bowman Field, at Louisville, Kentucky for an extremely

strenuous eight-week course. During the course the women learned how to

load and off-load patients onto a transport while undergoing

military training including survival skills, the use of parachutes, and

simulated combat since the women would be required to fly into combat

areas. Upon completion of their training, the women were assigned to

air evacuation units overseas, where they flew as crewmembers aboard

troop carrier C-47s operating into forward airfields on battlefields

everywhere from New Guinea to Sicily, and later on the European

continent. The use of female flight nurses exposed women to combat

dangers that had never been experienced by American women as a group.

Several were killed and a handful were captured and became prisoners of

war. Their skill and diligence saved the lifes of hundreds of wounded

GIs who would have died on the battlefield in previous wars.

While

the WASPS were in civilian status, large

numbers of women served with the US Army Air Forces in World War II

with full military status. The one group of women who shared the same

dangers as did male aircrew members were the female flight nurses who

flew with troop carrier squadrons in all of the combat theaters. For

the first year or so of the war, no medical personnel flew on air

evacuation missions, but the need was seen and a medical evacuation

training school was set up at Bowman Field, Kentucky. By

1944 more than 6,500 nurses were on duty with the USAAF, of which 500

were on flight status in the air evacuation role. Flight nurses were

selected from nurses on duty with the USAAF hospitals, and who recieved

the recommendation of the senior flight surgeon in their command. After

passing a flight physical, the women were sent to the School of Air

Evacuation at Bowman Field, at Louisville, Kentucky for an extremely

strenuous eight-week course. During the course the women learned how to

load and off-load patients onto a transport while undergoing

military training including survival skills, the use of parachutes, and

simulated combat since the women would be required to fly into combat

areas. Upon completion of their training, the women were assigned to

air evacuation units overseas, where they flew as crewmembers aboard

troop carrier C-47s operating into forward airfields on battlefields

everywhere from New Guinea to Sicily, and later on the European

continent. The use of female flight nurses exposed women to combat

dangers that had never been experienced by American women as a group.

Several were killed and a handful were captured and became prisoners of

war. Their skill and diligence saved the lifes of hundreds of wounded

GIs who would have died on the battlefield in previous wars.

The

Air WACs were an outgrowth of the Womens Auxiliary Army Corps, which

was created in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. Although they weren't

officially designated as Air WACs, women assigned to Army Air Forces

units were commonly referred to by that title. Originally, women in the

Army served in an auxiliary status much like the WASPS, but in 1943 the

WAAC was changed to the WAC as women were accepted into the Army with

full military status rather than as an auxilary. From the outset of the

WAAC program, the Army Air Forces was the one branch of the service

most receptive to the use of women. At first the Air Corps wanted women

to serve as aircraft warning spotters, a task at which they did

exceptionally well. Until March, 1943 the USAAF's sole WACs were

assigned to Aircraft Warning Service stations. As the war continued

WACs were assigned to as many non-combat fields as possible, including

aircraft maintenance, and in a few instances, aircrew duty on transport

aircraft where they served as flight clerks, or flight attendants.

Still, most

women served in the clerical and administrative fields in which they

had been trained in civilian life. At least 20 women were assigned to

air crew duty - probably as flight clerks on executive

transports - and there was at least one WAC crew chief during the war.

Unlike the WASP pilots, AAF WACs served overseas, not only in

civilized England, but in primitive New Guinea as well as North Africa,

India and war-torn China and Italy. The presence of WACs in the

overseas theaters led to improved discipline and courtesy among the

male personnel with which they worked shoulder-to-shoulder. The Air

Transport Command was a primary user of WACs, using women as parachute

riggers, aircraft mechanics, radio operators and cargo and passenger

processing technicians.

The

Air WACs were an outgrowth of the Womens Auxiliary Army Corps, which

was created in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. Although they weren't

officially designated as Air WACs, women assigned to Army Air Forces

units were commonly referred to by that title. Originally, women in the

Army served in an auxiliary status much like the WASPS, but in 1943 the

WAAC was changed to the WAC as women were accepted into the Army with

full military status rather than as an auxilary. From the outset of the

WAAC program, the Army Air Forces was the one branch of the service

most receptive to the use of women. At first the Air Corps wanted women

to serve as aircraft warning spotters, a task at which they did

exceptionally well. Until March, 1943 the USAAF's sole WACs were

assigned to Aircraft Warning Service stations. As the war continued

WACs were assigned to as many non-combat fields as possible, including

aircraft maintenance, and in a few instances, aircrew duty on transport

aircraft where they served as flight clerks, or flight attendants.

Still, most

women served in the clerical and administrative fields in which they

had been trained in civilian life. At least 20 women were assigned to

air crew duty - probably as flight clerks on executive

transports - and there was at least one WAC crew chief during the war.

Unlike the WASP pilots, AAF WACs served overseas, not only in

civilized England, but in primitive New Guinea as well as North Africa,

India and war-torn China and Italy. The presence of WACs in the

overseas theaters led to improved discipline and courtesy among the

male personnel with which they worked shoulder-to-shoulder. The Air

Transport Command was a primary user of WACs, using women as parachute

riggers, aircraft mechanics, radio operators and cargo and passenger

processing technicians.

Unlike WASPs, flight nurses and WACs were destined to become a

part of the post-war Army Air Forces, and ultimately of the United States Air

Force. In a report prepared at the end of the war, General Arnold reported that

women in the jobs they were qualified to do were "more efficient" than men in

the same jobs. As for flight nurses, their devotion to duty and efficiency

established a place for them with the post-war Air Transport and Troop Carrier

Commands.

Click Table of

Contents to return.

In the mid-1970s, after the conclusion of the Vietnam War, the

United States Air Force began accepting young women as pilot trainees. The

destination for the women who successfully completed undergraduate pilot

training would be primarily into the Military Airlift Command, where they would

take their place in the cockpits of military transports and light utility jets.

The women who entered the world of military airlift were following in the

footsteps of another generation, the women pilots of the Womens Auxiliary

Ferrying Service and the Womens Airforce Service Pilots of World War II.

In the mid-1970s, after the conclusion of the Vietnam War, the

United States Air Force began accepting young women as pilot trainees. The

destination for the women who successfully completed undergraduate pilot

training would be primarily into the Military Airlift Command, where they would

take their place in the cockpits of military transports and light utility jets.

The women who entered the world of military airlift were following in the

footsteps of another generation, the women pilots of the Womens Auxiliary

Ferrying Service and the Womens Airforce Service Pilots of World War II.

In 1940, before the United States went to war, the

Army Air Corps established the Ferrying Command, an organization

responsible for flying US-built airplanes to points where they could be

delivered to ferry pilots from the countries who were allied against

the Axis powers in Europe. Initially, the Ferrying Command depended

upon the Air Corps Combat Command combat squadrons for the pilots to

make the flights, on the basis that the long cross country flights from

the American West Coast to the East Coast and Canada provided valuable

training experience that the crews could take back with them to their

squadrons. But when Pearl Harbor plunged America into the war, the

combat pilots were needed to staff the under-strength fighter, bomber

and troop carrier squadrons which would fight the war so the Army

contracted with the national airlines and other civilian aviation companies to take over some of the ferrying

duties. In mid-1942 Ferrying Command became the Air Transport Command,

with the ferry mission placed under the Ferrying Division, commanded by

Colonel William H. Tunner. In June, 1940 the Ferrying Command had been

authorized to employ civilian pilots with significant flight

experience, but the practice was still untried when America went to

war. Right after Pearl Harbor the Army began recruiting civilian

pilots, and by the end of January, 1942 343 civilian pilots with

backgrounds in non-airline civil aviation had been assigned to ACFC's

Domestic Wing. The men, all of whom had a minimum of 500 hours of

civilian flight time, were employed on a 90-day temporary basis. If

found qualified to fly military aircraft at the end of the probationary

period, the men were offered commissions as service pilots, a

qualification somewhat lower than that required for combat pilots. The

amount of flight time required was lowered to as low as 200 hours for a

brief time, but by 1944 had been increased to 1,000 hours.

In 1940, before the United States went to war, the

Army Air Corps established the Ferrying Command, an organization

responsible for flying US-built airplanes to points where they could be

delivered to ferry pilots from the countries who were allied against

the Axis powers in Europe. Initially, the Ferrying Command depended

upon the Air Corps Combat Command combat squadrons for the pilots to

make the flights, on the basis that the long cross country flights from

the American West Coast to the East Coast and Canada provided valuable

training experience that the crews could take back with them to their

squadrons. But when Pearl Harbor plunged America into the war, the

combat pilots were needed to staff the under-strength fighter, bomber

and troop carrier squadrons which would fight the war so the Army

contracted with the national airlines and other civilian aviation companies to take over some of the ferrying

duties. In mid-1942 Ferrying Command became the Air Transport Command,

with the ferry mission placed under the Ferrying Division, commanded by

Colonel William H. Tunner. In June, 1940 the Ferrying Command had been

authorized to employ civilian pilots with significant flight

experience, but the practice was still untried when America went to

war. Right after Pearl Harbor the Army began recruiting civilian

pilots, and by the end of January, 1942 343 civilian pilots with

backgrounds in non-airline civil aviation had been assigned to ACFC's

Domestic Wing. The men, all of whom had a minimum of 500 hours of

civilian flight time, were employed on a 90-day temporary basis. If

found qualified to fly military aircraft at the end of the probationary

period, the men were offered commissions as service pilots, a

qualification somewhat lower than that required for combat pilots. The

amount of flight time required was lowered to as low as 200 hours for a

brief time, but by 1944 had been increased to 1,000 hours.

WASP

flying was exclusively within the United

States and occasionally into Canada. The director of Ferrying Division,

Brig. Gen. William H. Tunner, was impressed with the women under his

command

and sought to use them to the full extent of their abilities, including

on overseas ferry routes. In September, 1943 Nancy Love and Betty

Gilles,

two

of the most experienced female pilots assigned to ATC - Love founded

the WAFS and was director of women ferry pilots while Gilles was her

first recruit - were given a

mission to ferry a B-17 to England across the North Atlantic route. A

hand-picked crew - including Tunner's personal navigator - was

assigned to the mission to support the two women on what would have

been a history making event. The two female pilots set out from their

base at New Castle, Delaware in the B-17, expecting to take the Flying

Fortress all the way to Prestwick, Scotland. But when they got to

Newfoundland, Love and Gilles were ordered to surrender the airplane to

an all-male crew by personal order of General Arnold. Though Arnold

gave the order, just why he did so remains unclear since he had

previously given permission for the mission. Many of the former WAFS

pilots felt that Jackie Cochran put a halt to the mission because of

personal jealousy of Nancy Love's experience and notoriety within the

military. Cochran had flown her personal Lockheed Hudson to Scotland

earlier, and some women believed that she did not want to be

over-shadowed by Love. Others, those who came through Cochran's

training program, thought Arnold was afraid of the possible exposure of

the two women to interception by German fighters as they passed near

the Norweigan coast. (Such an explanation is very unlikely considering

that Norway is 500 miles east of the route from Iceland to the UK.)

Whatever the reason for the cancellation, the two

disappointed women returned to New Castle and no international ferry

flights were ever authorized for female pilots and crews.

WASP

flying was exclusively within the United

States and occasionally into Canada. The director of Ferrying Division,

Brig. Gen. William H. Tunner, was impressed with the women under his

command

and sought to use them to the full extent of their abilities, including

on overseas ferry routes. In September, 1943 Nancy Love and Betty

Gilles,

two

of the most experienced female pilots assigned to ATC - Love founded

the WAFS and was director of women ferry pilots while Gilles was her

first recruit - were given a

mission to ferry a B-17 to England across the North Atlantic route. A

hand-picked crew - including Tunner's personal navigator - was

assigned to the mission to support the two women on what would have

been a history making event. The two female pilots set out from their

base at New Castle, Delaware in the B-17, expecting to take the Flying

Fortress all the way to Prestwick, Scotland. But when they got to

Newfoundland, Love and Gilles were ordered to surrender the airplane to

an all-male crew by personal order of General Arnold. Though Arnold

gave the order, just why he did so remains unclear since he had

previously given permission for the mission. Many of the former WAFS

pilots felt that Jackie Cochran put a halt to the mission because of

personal jealousy of Nancy Love's experience and notoriety within the

military. Cochran had flown her personal Lockheed Hudson to Scotland

earlier, and some women believed that she did not want to be

over-shadowed by Love. Others, those who came through Cochran's

training program, thought Arnold was afraid of the possible exposure of

the two women to interception by German fighters as they passed near

the Norweigan coast. (Such an explanation is very unlikely considering

that Norway is 500 miles east of the route from Iceland to the UK.)

Whatever the reason for the cancellation, the two

disappointed women returned to New Castle and no international ferry

flights were ever authorized for female pilots and crews.  While

the WASPS were in civilian status, large

numbers of women served with the US Army Air Forces in World War II

with full military status. The one group of women who shared the same

dangers as did male aircrew members were the female flight nurses who

flew with troop carrier squadrons in all of the combat theaters. For

the first year or so of the war, no medical personnel flew on air

evacuation missions, but the need was seen and a medical evacuation

training school was set up at Bowman Field, Kentucky. By

1944 more than 6,500 nurses were on duty with the USAAF, of which 500

were on flight status in the air evacuation role. Flight nurses were

selected from nurses on duty with the USAAF hospitals, and who recieved

the recommendation of the senior flight surgeon in their command. After

passing a flight physical, the women were sent to the School of Air

Evacuation at Bowman Field, at Louisville, Kentucky for an extremely

strenuous eight-week course. During the course the women learned how to

load and off-load patients onto a transport while undergoing

military training including survival skills, the use of parachutes, and

simulated combat since the women would be required to fly into combat

areas. Upon completion of their training, the women were assigned to

air evacuation units overseas, where they flew as crewmembers aboard

troop carrier C-47s operating into forward airfields on battlefields

everywhere from New Guinea to Sicily, and later on the European

continent. The use of female flight nurses exposed women to combat

dangers that had never been experienced by American women as a group.

Several were killed and a handful were captured and became prisoners of

war. Their skill and diligence saved the lifes of hundreds of wounded

GIs who would have died on the battlefield in previous wars.

While

the WASPS were in civilian status, large

numbers of women served with the US Army Air Forces in World War II

with full military status. The one group of women who shared the same

dangers as did male aircrew members were the female flight nurses who

flew with troop carrier squadrons in all of the combat theaters. For

the first year or so of the war, no medical personnel flew on air

evacuation missions, but the need was seen and a medical evacuation

training school was set up at Bowman Field, Kentucky. By

1944 more than 6,500 nurses were on duty with the USAAF, of which 500

were on flight status in the air evacuation role. Flight nurses were

selected from nurses on duty with the USAAF hospitals, and who recieved

the recommendation of the senior flight surgeon in their command. After

passing a flight physical, the women were sent to the School of Air

Evacuation at Bowman Field, at Louisville, Kentucky for an extremely

strenuous eight-week course. During the course the women learned how to

load and off-load patients onto a transport while undergoing

military training including survival skills, the use of parachutes, and

simulated combat since the women would be required to fly into combat

areas. Upon completion of their training, the women were assigned to

air evacuation units overseas, where they flew as crewmembers aboard

troop carrier C-47s operating into forward airfields on battlefields

everywhere from New Guinea to Sicily, and later on the European

continent. The use of female flight nurses exposed women to combat

dangers that had never been experienced by American women as a group.

Several were killed and a handful were captured and became prisoners of

war. Their skill and diligence saved the lifes of hundreds of wounded

GIs who would have died on the battlefield in previous wars.  The

Air WACs were an outgrowth of the Womens Auxiliary Army Corps, which

was created in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. Although they weren't

officially designated as Air WACs, women assigned to Army Air Forces

units were commonly referred to by that title. Originally, women in the

Army served in an auxiliary status much like the WASPS, but in 1943 the

WAAC was changed to the WAC as women were accepted into the Army with

full military status rather than as an auxilary. From the outset of the

WAAC program, the Army Air Forces was the one branch of the service

most receptive to the use of women. At first the Air Corps wanted women

to serve as aircraft warning spotters, a task at which they did

exceptionally well. Until March, 1943 the USAAF's sole WACs were

assigned to Aircraft Warning Service stations. As the war continued

WACs were assigned to as many non-combat fields as possible, including

aircraft maintenance, and in a few instances, aircrew duty on transport

aircraft where they served as flight clerks, or flight attendants.

Still, most

women served in the clerical and administrative fields in which they

had been trained in civilian life. At least 20 women were assigned to

air crew duty - probably as flight clerks on executive

transports - and there was at least one WAC crew chief during the war.

Unlike the WASP pilots, AAF WACs served overseas, not only in

civilized England, but in primitive New Guinea as well as North Africa,

India and war-torn China and Italy. The presence of WACs in the

overseas theaters led to improved discipline and courtesy among the

male personnel with which they worked shoulder-to-shoulder. The Air

Transport Command was a primary user of WACs, using women as parachute

riggers, aircraft mechanics, radio operators and cargo and passenger

processing technicians.

The

Air WACs were an outgrowth of the Womens Auxiliary Army Corps, which

was created in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. Although they weren't

officially designated as Air WACs, women assigned to Army Air Forces

units were commonly referred to by that title. Originally, women in the

Army served in an auxiliary status much like the WASPS, but in 1943 the

WAAC was changed to the WAC as women were accepted into the Army with

full military status rather than as an auxilary. From the outset of the

WAAC program, the Army Air Forces was the one branch of the service

most receptive to the use of women. At first the Air Corps wanted women

to serve as aircraft warning spotters, a task at which they did

exceptionally well. Until March, 1943 the USAAF's sole WACs were

assigned to Aircraft Warning Service stations. As the war continued

WACs were assigned to as many non-combat fields as possible, including

aircraft maintenance, and in a few instances, aircrew duty on transport

aircraft where they served as flight clerks, or flight attendants.

Still, most

women served in the clerical and administrative fields in which they

had been trained in civilian life. At least 20 women were assigned to

air crew duty - probably as flight clerks on executive

transports - and there was at least one WAC crew chief during the war.

Unlike the WASP pilots, AAF WACs served overseas, not only in

civilized England, but in primitive New Guinea as well as North Africa,

India and war-torn China and Italy. The presence of WACs in the

overseas theaters led to improved discipline and courtesy among the

male personnel with which they worked shoulder-to-shoulder. The Air

Transport Command was a primary user of WACs, using women as parachute

riggers, aircraft mechanics, radio operators and cargo and passenger

processing technicians.